Updates to the Patent Prosecution Highway

Posted: 2/10/2026

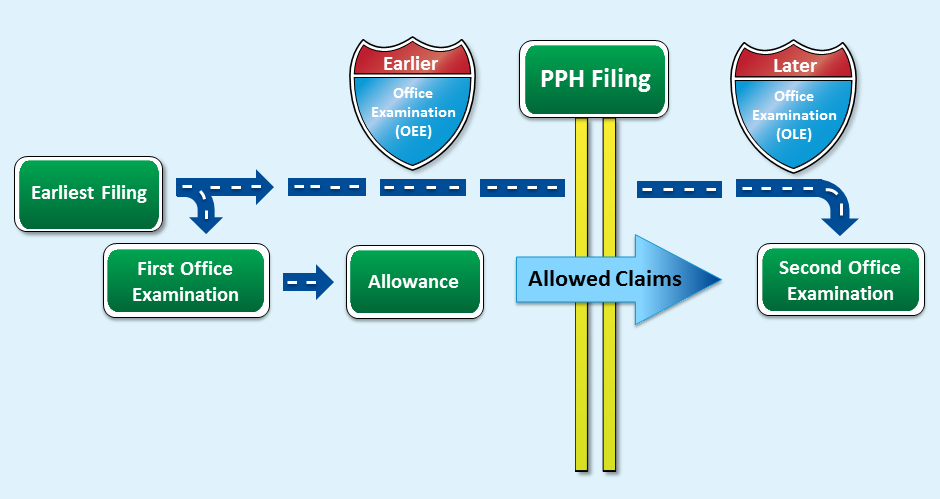

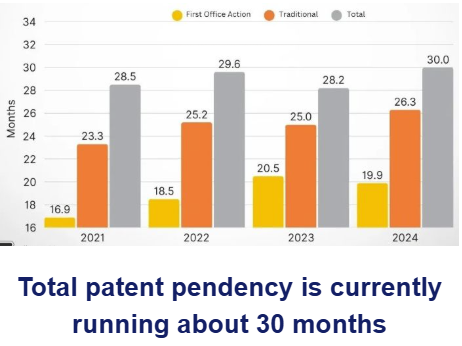

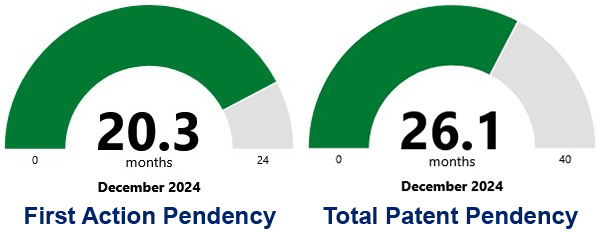

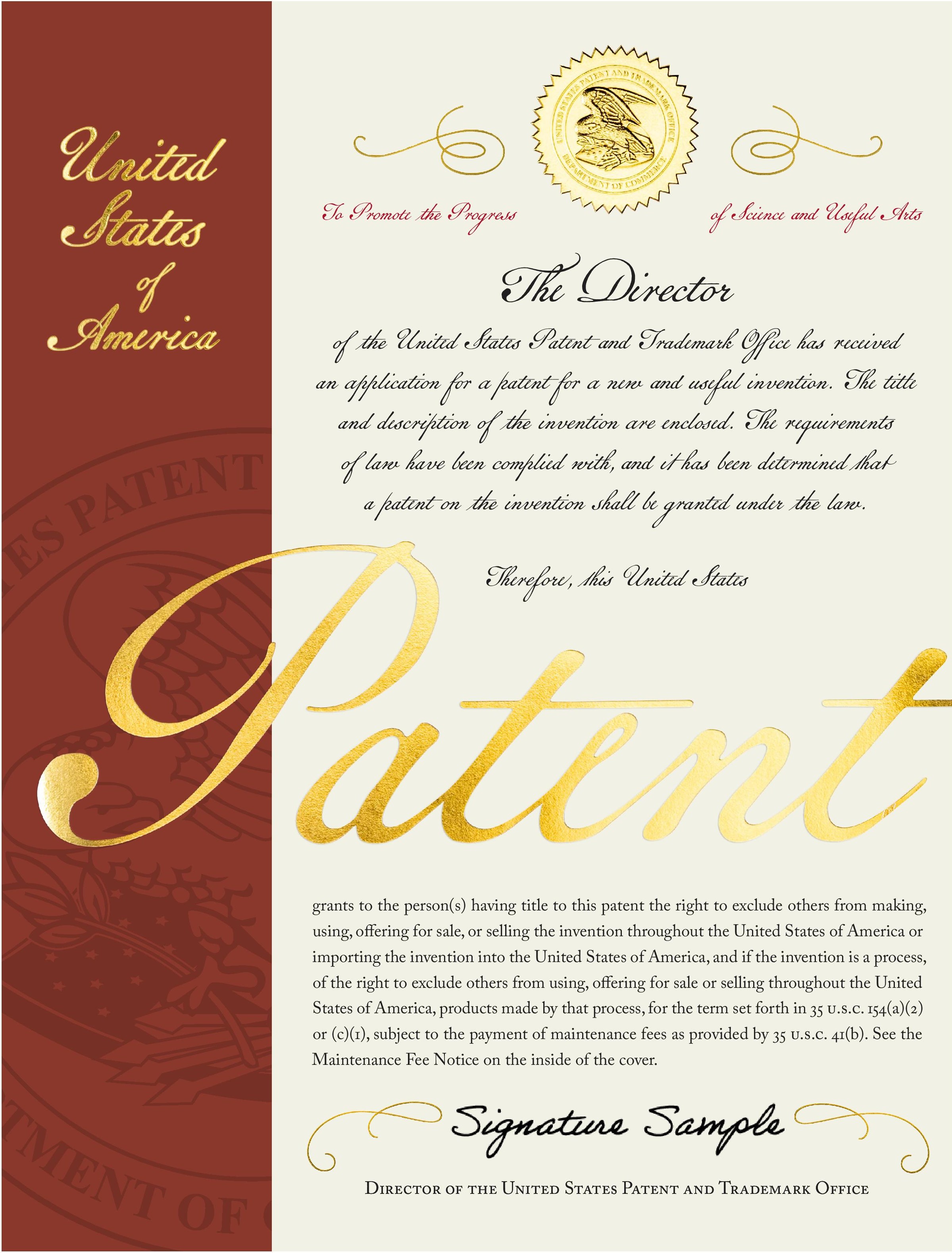

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has announced improvements to the docketing of Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) applications with a granted petition so that PPH first action pendency in a particular technology is approximately half the time of current non-PPH applications.

In case you are not aware of the Patent Prosecution Highway – all inventors should be – this program offers an effective strategy for patent applicants to get their patents granted faster in global markets by allowing applicants who receive a determination of allowable claims in an application from one Intellectual Property (IP) office to obtain expedited examination of corresponding claims filed in an application pending in another participating IP Office.

At the USPTO, PPH applications represent only about 2% of filings with an average first action pendency of around 7-½ months. As the backlog of unexamined patent applications at the Patent Office has increased, so too has the pendency times for non-PPH applications. Pendency for non-PPH applications has grown from under 15 months in 2020 to over 22 months in 2025. As a result, the expedited examination benefits of PPH applications have become disproportionate to non-PPH applications even in light of the fact that the volumes are low when compared with non-PPH applications.

The new docketing approach implemented at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office addresses this imbalance by aligning these timelines more proportionately on a technology-based criterion. Patent Prosecution Highway applications will still get the benefit of expedited examination as part of the PPH program, but as non-PPH pendency times improve, so too will PPH pendency times. The thinking is that this change provides a more equitable examination for all applicants.

Patent applicants have to apply for admission to the PPH, and the four foreign cooperating patent offices are:

♦ European Patent Office (EPO)

♦ China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA)

♦ Japan Patent Office (JPO)

♦ Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO)

Since its founding in 2006, 107,685 patent applicants applied for the Patent Prosecution Highway, and 97,983 were accepted. Any U.S. Patent applicant that plans to also apply for an EPO, China, Japan, or Korea office, should apply to the Patent Prosecution Highway program!

Radar Helped Win the War. Now It Predicts the Weather

Posted: 1/27/2026

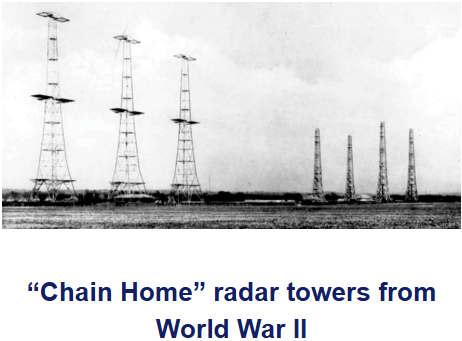

RADAR is an acronym for “Radio Detection And Ranging”. It is a technology that played a key role in winning World War II. The Alleys had radar and the Germans and Japanese did not.

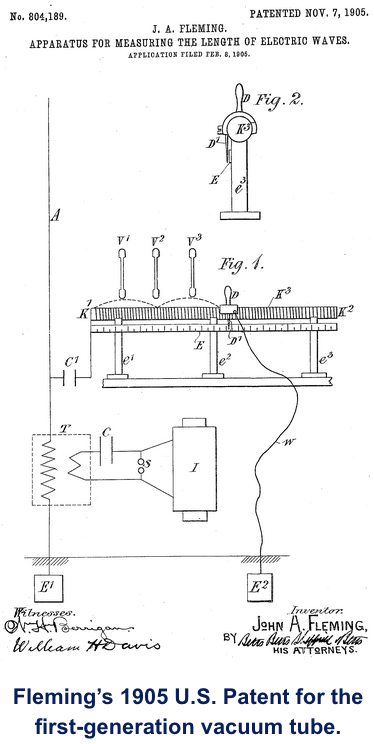

Radar was initially patented by one Robert Watson-Watt, a descendant of James Watt of the steam engine. He was awarded British Patent GB426328A for "Improvements in wireless direction and position finding" on April 2, 1935 – just in time for the Blitz, a bombing campaign launched by the Germans in 1940.

Possibly prompted by rumors that the Germans had produced a “death ray,” in 1934, the British Air Ministry asked Watson-Watt to investigate such a technology. The Air Ministry had already offered 1000 pounds to anyone who could demonstrate a ray that could kill a sheep 100 yards away. Watson-Watt concluded that such a device was not feasible, but wrote a memo that he had turned his attention to “the difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio-detection as opposed to radio-destruction.”

could kill a sheep 100 yards away. Watson-Watt concluded that such a device was not feasible, but wrote a memo that he had turned his attention to “the difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio-detection as opposed to radio-destruction.”

In February of 1935 Watson-Watt demonstrated to an Air Ministry committee the first practical radio system for detecting aircraft. The Air Ministry was impressed, and in April Watson-Watt received a patent for the system and funding for further development. Soon Watson-Watt was using pulsed radio waves to detect airplanes up to 80 miles away.

The British constructed a network of radar stations along the east coast of England using Watson-Watts’ design. These stations, known as Chain Home, successfully alerted the Royal Air Force to approaching enemy bombers, and helped defend Britain against the German Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain.

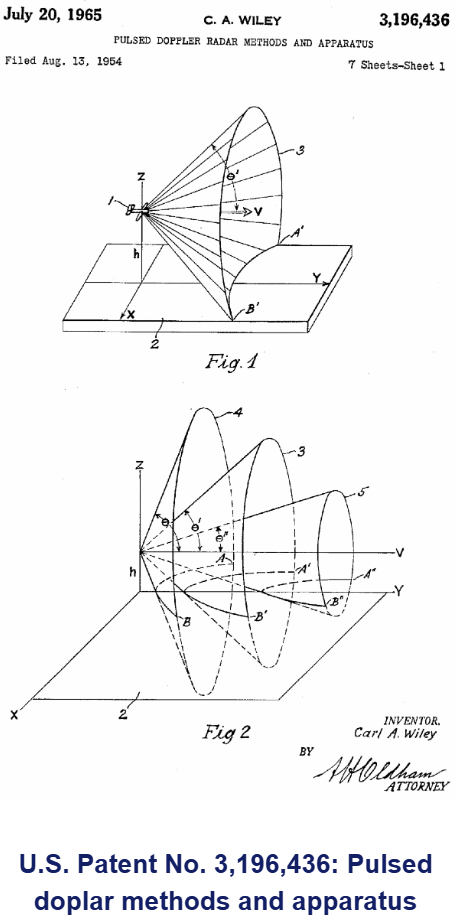

Watson-Watt’s original concept for radar became a reality 30 years later when Carl Riley received U.S. Patent No. 3,196,436 for "Pulsed doplar radar methods and apparatus” on July 20, 1965. Today, we call that technology transfer! The term “doplar” was named after Christian Doppler who way back in 1842 described how the observed frequency of wave changes based on the relative motion between the source and the observer.

Doplar radar is now in common use to track the weather – like the monster snow storm that just blasted across the Eastern U.S.

Why Google Patents and Not the Patent Office Website?

Posted: 1/14/2026

Our Best Wishes for 2026: All the economic indicators point to a very robust economy for 2026. With that in mind, we wish a healthy and prosperous year to our readers, our clients, and Corporate America.

Speaking of 2026: This year – you probably know this already – is the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. We are reminded of what Ben Franklin said as the delegates to the Continental Congress signed the document: “We must all hang together or we will most assuredly all hang separately.” The celebration is being spearheaded by America 250.

This year will also be the 25th anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Special Recognition for IPOfferings! Business Management Review is a print and digital publication for business managers across all disciplines that offers industry insights, peer-driven strategies, and coverage of the latest trends in business management solutions. Business Management Review chose IPOfferings as the “Top Patent Brokerage and Valuation Service” provider for 2026. Our selection for this honor was based on reader input.

We were both surprised and honored. Business Management Review announced this honor in “Turning Patents into Valuable Assets.”. The article provides a most comprehensive overview of our business.

Thank you Business Management Review for this recognition.

Practical Advice for 2026…and Beyond: You’ve already made – and a few of you have already broken – your 2026 New Year’s Resolutions. So here is some advice for inventors and assignees.

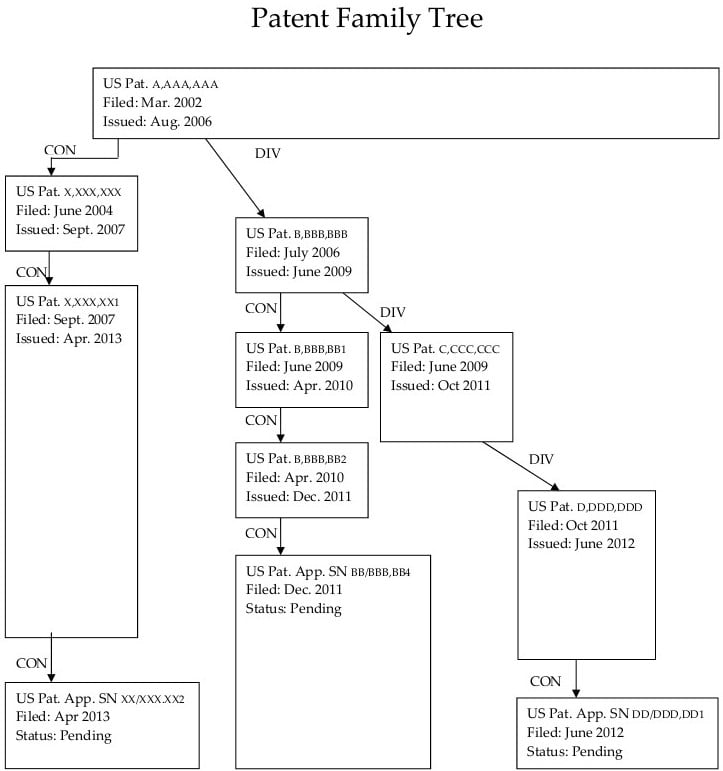

♦ Always file for a Continuation: As soon as your patent application is approved, but before your patent is granted, apply for a Continuation. A Continuation filing creates a new patent application that includes the Priority Date and claims of the original patent. A Continuation provides two benefits.

1. It enables the inventor to add claims, expanding on his or her original invention. It is not uncommon for an inventor – once his or her patent is granted and out in the marketplace – to discover some added tweaks or refinements or capabilities that were missed in the original patent filing. The inventor can use the Continuation to apply for a second patent with added or expanded claims that has the same Priority Date as the original patent.

2. It adds value and curb appeal to a patent since the company that acquires the patent-and-continuation package has the ability to add features to the original patented invention. As a company goes through the process of turning a patented invention into a product or service, it often comes across features that would add additional value. The original patent is fixed forever in time. It cannot be modified. But the Continuation can be used to create a second patent with the same Priority Date as the original patent, but with additional claims covering additional features

What, you might ask, is so important about a patent’s Priority Date. If that patent has to be enforced, a critical element in the patent infringement lawsuit will be if the infringer’s product existed before the Priority Date of the patent-at-trial.

♦ Always file for a PCT Application: Before your U.S. Patent is granted, file for a PCT Patent Application. This filing makes it much easier to file for a patent for the same invention in other countries. The company that buys your patent may very likely have a presence in other countries, and can use your PCT Patent Application to establish a priority date for a patent in any of those countries.

Just to be clear, a PCT Patent Application does NOT give you patent protection in the 158 countries that are signatories to this treaty. What it DOES do is make it significantly easier to file for – and secure – patent protection in foreign nations. Adding a PCT Patent Application to your granted U.S. Patent creates a patent family with additional curb appeal and value.

♦ Do NOT Try to Go to Market with a Provisional Patent Application: We are contacted every day – literally every day – by inventors with Provisional Patent Applications who want to sell or license their patent filings. Attempting to monetize a Provisional Patent Application is simply NOT a practical undertaking! This is explained at the Advice for the First-Time Inventor page at our website. We suppose it might possibly be done if the patentee and the prospective buyer were willing to jump through enough hoops, but it’s too much aggravation for us.

Round-Up of Items for 2025

Posted: 12/10/2025

Lists are very popular as a year comes to an end. Who died. The most popular baby names. What the dictionary editors selected as the “word of the year”. And speculation over who Time magazine will select as their “Person of the Year.” We are going to use this year-end column to catch up on bunch of stuff in no particular order. Here goes.

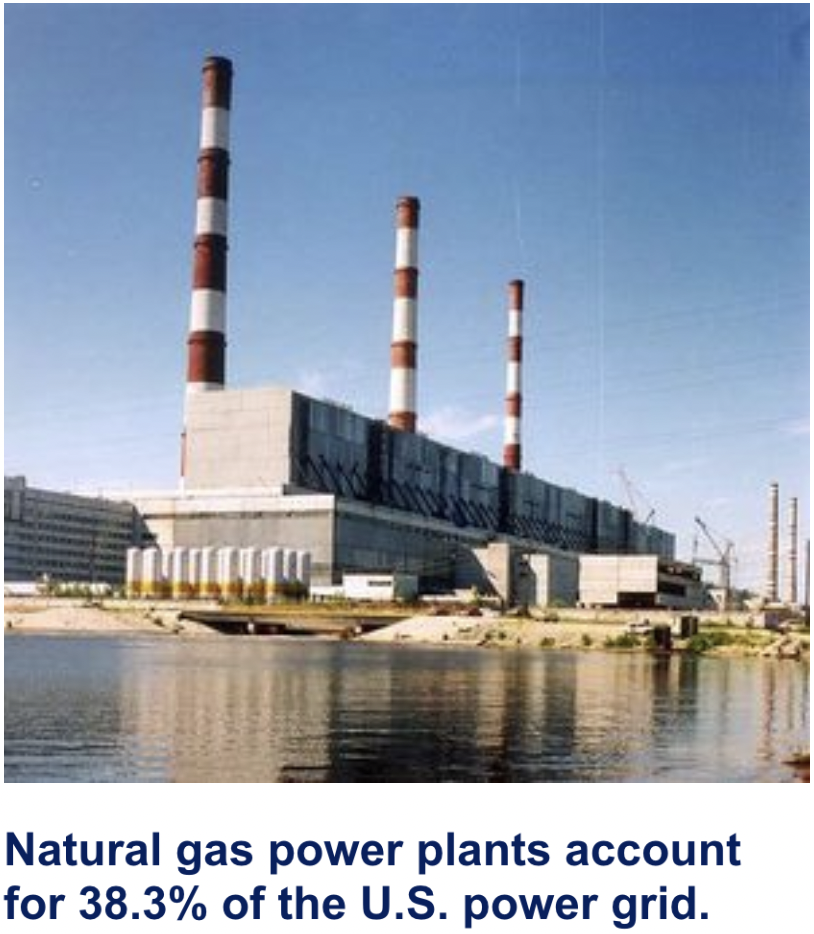

Yes, electric vehicles do not burn gas or diesel. Or trash like Doc’s time-traveling DeLorean in Back to the Future. But…the electricity used to charge an electric vehicle’s battery is NOT green.

The U.S. Energy Information Agency reports that 60% of the electrical current available to U.S. consumers is generated from fossil fuel – primary natural gas. That means that 60% of the electricity used by an EV is NOT green.

If an electric car owner were to put solar panels on his or her roof, or construct a wind turbine in his or her backyard, and use power exclusively for the solar panels or the wind turbine to charge the Tesla, then and only then would the vehicle be green. This is not directly related to patents, but we just had to get it off our chest.

Non-U.S. Patents Have Very Little Value: We are contacted at least once a day by an inventor with an Australian or Indian or South African or German Patent, and those inventors are very upset when we inform them that we do not represent non-U.S. Patents unless they are part of a portfolio that includes a U.S. Patent.

Non-U.S. Patents Have Very Little Value: We are contacted at least once a day by an inventor with an Australian or Indian or South African or German Patent, and those inventors are very upset when we inform them that we do not represent non-U.S. Patents unless they are part of a portfolio that includes a U.S. Patent.

The reasoning behind this is not that we are inward-thinking Americans – although we all are and we love this country – but because of the fatal flaw in a foreign patent. Let’s take a German Patent. It is only enforceable in Germany. That means that a business can blatantly infringe the patent by manufacturing a product based on the patent, and selling a patent based on the patent, and as long as the company does not manufacture or sell the product in Germany, the there nothing the inventor can do! And the entire world – less Germany – is a pretty big marketplace!

The infringer can sell the product in the U.S., Canada, the UK, France, Italy, the Netherlands, all of Asia, all of South America, all of Africa, and Australia and New Zealand. And the infringer can do nothing.

In fact, having a single-nation patent is worse than no patent at all since patents are public documents, so securing a German Patent broadcasts your invention to anyone and everyone. That inventor would have been better off keeping it a Trade Secret.

Since the U.S. is the largest global marketplace, a single U.S. Patent is the only single-nation patent that has commercial value. Sorry, but those are the facts.

What About a PCT Patent Application? The response we get from many inventors of single-nation patents is that they also filed a PCT Patent Application, so they have worldwide patent protection for their invention. All a PCT Patent Application does is give the inventor the right to apply for a patent in any of the Patent Cooperation Treaty nations, it does NOT grant patent protection in any of those countries. It does prevent the company that is blatantly infringing the aforementioned hypothetical German Patent from applying for a patent in any of the PCT countries, but it does NOT prevent the company from infringing the German Patent outside of Germany.

We Do NOT Represent Provisional Patent Applications: It is simply NOT a practical undertaking to attempt to take to market a Provisional Patent Application. We are contacted at least once a day – sometimes multiple times a day – by inventors with Provisional Patent Applications. Many of them begin their correspondence claiming to have a “patent” or “patents” but supplying no patent numbers. When we press for a patent number, the inventor admits that he or she really just has a Provisional Patent Application – often one that was just filed a few days ago!

We at IPOfferings are real-world practical people, and it is simply not a practical undertaking to attempt to take to market a Provisional Patent Application. A buyer wants to know and is entitled to know what he or she or it is buying, and we cannot send that prospective buyer to Google Patents to see the entire filing – the Abstract, the Claims, the Prior Art, the Forward Citations, the Priority Date, the figures, and the narrative – until the application becomes Non-Provisional and is published. This is all explained at the Advice for the First-Time Inventors page at our website.

We explain this to the Provisional Patent Applicant, and the response we so often receive is that we do not understand. The invention covered by this Provisional Patent Application is the single-greatest invention in the history of mankind. How could we walk away? We are not walking away. We are waiting until the patent application is published so representing it is practical, common-sense undertaking.

We Are Still Trying to Figure This Out! The Wright brothers invented the airplane, and proved it to the world with the first manned flight on the beach at Kitty Hawk, South Carolina, on December 17, 1903 – 122 years ago next Wednesday. They applied for a patent for a “Flying Machine” on March 23, 1903. They received U.S. Patent No. 821,393 on May 22, 1906 – three years and two months later.

What took the Patent Office so long? There was NO Prior Art. Three years to approve that patent. Really?

Our Best Wishes: We wish the very best to our readers and clients for a healthy and prosperous 2026. It will be the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

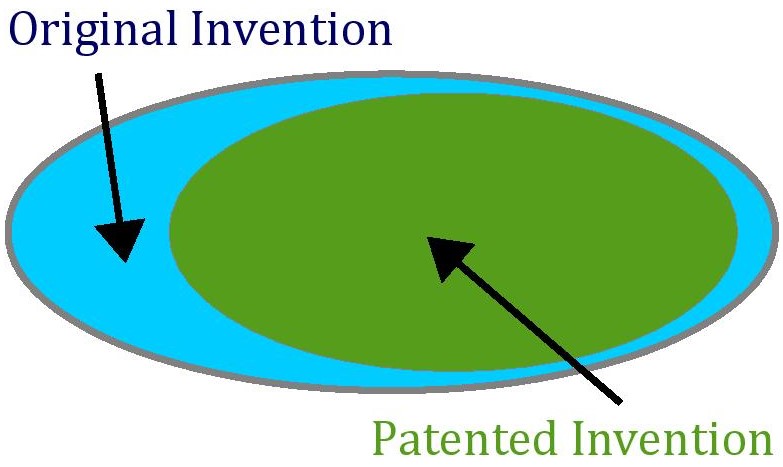

There Is Your Invention, and Then There’s Your Patent

Posted: 11/18/2025

It is a common occurrence for IPOfferings to be contacted by an inventor or a company about its patent or patents to inquire about having IPOffering represent the patentee in the sale or licensing of his or her or its patent(s). We are continually surprised by the number of such inquiries in which the email does NOT include the patent number or numbers! We respond to the inquiry and ask for the patent number, and the recipient responds by sending us a Powerpoint or a video or a valuation of his or her or its patent. But still NO patent number.

What many patent owners do not grasp is that a patent broker does NOT go to market with your invention. A patent broker goes to market with your patent – and there is often a significant difference between the two. You can tell us all day long about your invention. You can send us a write-up, a video, a Powerpoint, an Excel file, a valuation, or any other document, but it does not replace the need for us to see that actual patent or patents or patent application! And we do NOT need an NDA to see the patent(s) because patents are public documents.

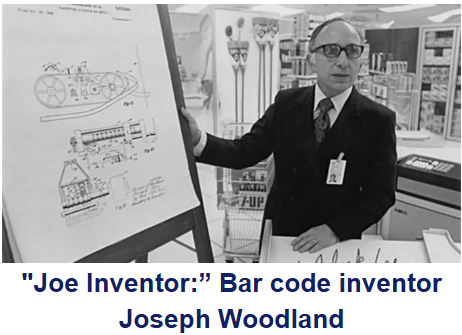

The reason we need to see the actual granted patent or the actual filed patent application is this: It is often the case that the patent does not match the invention we are being told about by the inventor or assignee. How can this be? Joe Inventor came up with an idea for a new product, so he hired a patent attorney who filed a patent application. Surely his invention is covered by his patent. Not necessarily!

Here is what happens. The patent attorney gets a description of the patent from the inventor, and from that description he or she files a patent application. The patent attorney probably runs the list of claims that are being submitted to the Patent Office past the inventor to make sure they are accurate.

But then what is known as “patent prosecution” begins. The patent application is assigned to a patent examiner, and it is the patent examiner’s job to determine if the invention meets three essential qualities.

1. It is novel.

2. It is practical.

3. It is not obvious.

The major issue is almost always the “novel” aspect. The patent examiner will challenge any claims that are not “novel” (new and not in current use) and it will be the patent attorney’s task to defend those claims. Some of the original claims may have to be dropped while others will have to be modified in order to get the patent granted. And it is the job of the patent attorney to do just that. The result, however, may be a granted patent that does not exactly follow the invention that is rolling around in the inventor’s mind.

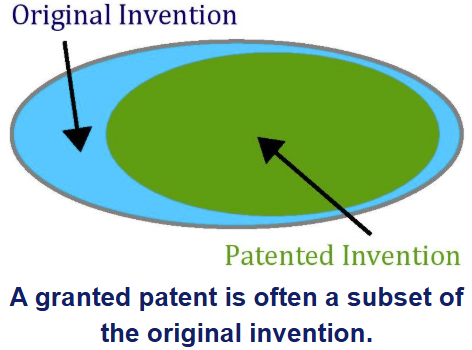

Parallel to this is the issue that the inventor is always improving, tweaking, expanding, and fine-tuning his or her invention, so during the two or three years of total patent pendency (the period of time from when the patent application is filed to when it either receives a Final Rejection or it is granted as a patent) the invention morphs into something different than the original invention described to the patent attorney 25 or 35 months ago.

Sooo. Based on this reality we have two suggestions.

1. Get Your Patent in Front of the Broker: Get the patent – the actual granted patent, or the published patent application, or a link to either at Google Patents – in front of the patent broker up front. It is the patent the broker will be taking to market – not your invention that could be significantly different.

2. File for a Continuation: You can use a continuation to create a second patent that covers any enhancements to the invention. As the invention morphs in the inventor’s mind, he or she can always use a continuation to secure a second patent that (a.) includes those enhancements and (b.) includes what did not make in into the first patent – and this patent has the same Priority Date as the original patent. A second patent examiner might view a claim differently or revised wording can be used to get a claim accepted. Should you use your continuation to secure a second patent, be sure to apply for a continuation on the second patent. You always, always, always want to have an open continuation either for your own use or for the entity that acquires your patent.

She Invented Voice-over-IP – to Name Just a Few Inventions!

Posted: 10/28/2025

Fans of this column know that we are insistent at referring to inventors as “he or she” because there are, indeed, many female inventors and the Official IPOfferings Stylebook calls for the conscientious use of “him or her” or “it, him, or her” when referring to patentees. This issue of IPMarketPlace features an 11-patent portfolio by a woman inventor.

We are taking this opportunity to introduce you to Marian Croak, the inventor of Voice-over-IP or “VoIP”. Dr. Croak grew up in New York City. She earned her undergraduate degree from Princeton University and went on to earn her Ph.D. in Quantitative Analysis and Psychology from the University of Southern California.

She initially went to work for Bell Labs, the moved to AT&T, and has been the Vice President of Engineering at Google for the past 11 years. She is a named inventor on over 200 patents, but her most notable invention was VoIP.

She was a co-inventor of U.S. Patent No. 7,599,359 for a “Method and apparatus for monitoring end-to-end performance in a network” – the foundational technology behind Voice-over-IP. We could not help but notice that the application for this patent was filed in 2004, but the patent was not granted until, 2009 – five years later! This patent would have been enforceable through 2027 thanks to a term extension, but AT&T let it lapse in 2021. The patent currently has 43 Forward Citations.

Dr. Croak is a member of the National Inventors Hall of Fame®. Here is a link to her page there.

National Inventors Hall of Fame is a trademark of National Inventors Hall of Fame, Inc.

She Invented the Disposable Diaper – to Name Just a Few!

Posted: 10/28/2025

Marion O’Brien grew up in South Bend, Indiana, and her father was the inventor of the South Bend Lathe. She received a B.A. in English from Rosemont College and 19 years later earned a Masters in Architecture from Yale.

As a young mother, Marion Donovan faced mountains of smelly diapers. She came up with the idea of a plastic cover for diapers that would trap the moisture and other debris so they could be tossed in the trash. She filed for and received U.S. Patent No. 2,575,164 for a “Diaper Housing”.

Ms. Donovan sold her patent for $1 million (roughly $12 million in today’s dollars) to a company that resold it to Procter & Gamble and it was used to create “Pampers®” disposable diapers. Ms. Donovan filed her patent application 1949 and the patent was granted in 1951 – just two years later. We cannot help ourselves when it comes to patent pendency. The patent expired in 1968, it currently has 44 Forward Citations, and the technology became a big money-maker for P&G.

Marion Donovan was awarded a total of 27 U.S. Patents including a patent for a combined checkbook and record-keeping book as well as floss and facial tissue patents. She is also a member of the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Here is a link to her page.

Pampers is a trademark of Proctor & Gamble Company.

The Patent Office Remains Open!

Posted: 10/7/2025

The non-essential units of the federal government are shut down until Congress either passes a new budget or a Continuing Resolution to temporarily fund the government. While it is not an “essential” service as are the military and law enforcement agencies like the FBI and DEA, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) remains open and in full operation for another reason. It is one of the few self-funded agencies of the U.S. federal government.

The USPTO does not use taxpayer funds. It is funded by the fees it collects from patent applications, patent holders, and others who pay for the services they receive from the Patent Office. And since the Patent Office is currently running a surplus, it has money in the bank. So, it will continue to operate until it runs out of funds which is not likely to be any time soon.

Being the curious sorts we are, we wondered how many other government agencies are self-funded, and there are actually quite a few. They include…

- U.S. Postal Service

- Passport Bureau

- Federal Reserve

- Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC)

- National Credit Union Administration

- Office of the Controller of the Currency

- Federal Housing Finance Agency (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac)

- Farm Credit Administration

Who knew?

Squires Takes Over at the Patent Office

Posted: 10/7/2025

After a delay of several months, John Squires was finally sworn in as Under-Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. As a Cabinet Officer, he was appointed by the new incoming President and needed to be confirmed by the Senate.

Here is an excerpt from Director Squire’s swearing-in speech:

I firmly and without reservation believe in a strong, robust, expansive, and resilient intellectual property system – and everything that goes with it. Patents and trademarks form the backbone of our competitive American economy. Our patent system has helped catalyze inventions that fuel industries and improve the quality of life, while our trademark system empowers businesses to build trust, protect their brands, and distinguish themselves in a crowded marketplace. The protections we offer enable entrepreneurs to compete, investors to believe, and consumers to have confidence in the products and services they rely on every day.

Our Office is not just an administrative agency; we are a strategic arm of national economic policy; we are the Department of Commerce’s Central Bank of Innovation. Every piece of IP we put into circulation is a potential job, a new business, a competitive advantage, or an investible asset. And yet another win for both society and the Constitutional foresight of our Founders.

Here, we drive prosperity and progress. In today’s interconnected world, the ripple effects of what we do extend far beyond our borders. Our decisions influence international standards, impact global supply chains, and help foster innovation and commercial ecosystems that contribute to economic growth worldwide. That’s why Commerce is our mothership - and that’s why we are an agency like no other.

The credibility and consistency of our work give individuals, businesses, and institutions the confidence to invest, to dream big, and to bring transformative ideas and powerful brands to market. What we do here matters - not just to applicants, but to the world.

As I testified to in my opening Statement to Senate Judiciary, there’s a saying that every patent begins its life as a trade secret. Inventors face a choice: keep their ideas locked away or bring them here – to our patent factory. And when they choose us, they place their trust in our ability to help them transform bold ideas into strong, enforceable rights. That’s our mission.

We take in raw innovation – and with diligence and care – help shape, hone, and hew it into durable and definable intellectual property. And when mistakes happen – and they will – there’s no need to be afraid of them. We will use the corrective measures Congress has provided – measurably, fairly, and judiciously – to improve our processes along the way – both front-end and back-end.

Inventors – as well as brand owners – don’t just seek rights; they make a trade with the public – disclosing their ideas and identities in exchange for time-limited protection. We are the guardians of that social contract.

We like this guy!

Patent Town Has a New Sheriff

Posted: 9/23/2025

Every American should know – we will excuse the non-U.S. readers of this newsletter – that Cabinet Secretaries serve at the pleasure of the President. Back on January 20, all the Cabinet Secretaries appointed by President Biden resigned, and they were replaced by acting Cabinet Secretaries until permanent replacements who were nominated by President Trump are confirmed by the U.S. Senate.

The Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is also the Under-Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property – a presidential appointee. So back on January 20, Kathi Vidal, the Patent Office Director appointed by Joe Biden, stepped down. She was replaced by Coke Morgan Stewart who became the Acting Director.

Well, it took a few months, but the Senate finally confirmed a new Under-Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office last week. He is John Squires, a partner at the Dilworth Paxson law firm. He is eminently qualified to become the next Patent Town Sheriff as he is well recognized as one of the world’s leading practitioners in advanced technologies and intellectual property including AI, blockchain, fintech, and cybersecurity. He has broad experience and expertise in all aspects of intellectual property including IP transactions, licensing, patent-asset creation, IP acquisition, commercial litigation, regulatory issues, and risk management. Mr. Squires led the creation of the first patent asset-backed finance platform for one of the world’s leading funds.

All nominees first go before a Senate Committee, and Squires was voted out of the Senate Judiciary Committee by a vote of 20 to 2. His confirmation by the full Senate was part of the “nuclear option” the Republicans recently used to get 48 stalled nominees confirmed. Squires will take control of the 13,000-employee U.S. Patent and Trademark Office as soon as he is sworn in. At that time, Coke Morgan Stewart will step down as Acting Director to assume a permanent role as Deputy Director.

In his hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Squires identified his priorities as USPTO Director as:

1. Reducing the patent application backlog.

2. Improving quality with “Born Strong” patents.

3. Reducing uncertainty under Section 101.

4. Introducing AI tools where it is practical to improve and speed up patent examinations.

In a written response to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Squires laid out his vision for restoring the USPTO “to its rightful place atop the world as executor of our Nation’s constitutional mandate and to boost America’s ingenuity engine with the intellectual property that drives economic growth, technological progress, and global competitiveness.”

We wish him well.

Three Common Misconceptions We Need to Correct

Posted: 9/9/2025

We receive a lot of mail, and there are three common misconceptions we see literally on a daily basis. So, in this installment of Patent Leather, we shall correct them.

♦ Patent Pending: We are amazed at how many inventors write to us and claim they have a “Patent Pending” or worse-yet a “Patent Pending patent!” “Patent Pending” is not a thing. It is an adjective that describes a product. Only a product can be “Patent Pending” – never a patent. The definition of “Patent Pending” is in the Glossary at our website.

A company comes up with an invention, and they file for a patent for that invention. The company then goes to market with a product based on that invention. Since all the company has is a patent application, it cannot mark the product with a patent number. So, they mark the product “Patent Pending” to let the world know that a patent is in process and to – ideally – scare off competitions from jumping into the market with a directly competing product!

Once the manufacturer of this product is granted a patent, “Patent Pending” is replaced on the product with the patent number. This is known as “Marking” or “Patent Marking” – also in the Glossary. It lets competitors know that the product is covered by a patent. If a product is NOT marked, and competitor goes to market with a similar product that infringes the patent, the patent owner’s claim is weakened because the patented product was not properly marked!

An inventor never, never, never has a “Patent Pending” or a “Patent Pending patent!” Never!

An inventor has either a patent application or a patent. To be more specific, a Provisional Patent Application, a Provisional Patent Application, or a granted Patent. An inventor never, never, ever, ever has a Patent Pending!

♦ Small Nation Patents: We get emails on a regular basis from inventors who have patents in small countries – Portugal, Indonesia, Australia, Columbia, you name it. And we have to tell them that their stand-along single-nation patent has NO commercial value. They are sometimes very upset. We do not tell the owner of a Swedish Patent, or an Israeli Patent, or a South Africa Patent that they need to contact us when they have a U.S. Patent because we are Ugly Americans.* We tell them to contact us when they have a U.S. Patent because the U.S. is the world’s largest economy.

Let’s take the case of a South African Patent. A patent is a public document, so once South Africa grants Joe Smith a patent, it is a public document for the world to see. Company X finds that patent, sees the potential in it, and immediately goes to market with a product based on that patent. As long as Company X does not manufacture that product in South Africa, or sell that product in South Africa, Joe Smith can do nothing! Company X can sell the product in the U.S., all of Europe, the Far West, and South America – over 150 countries. And as long as Company X does not manufacture or sell its infringing product in South Africa, the inventor can do nothing – except maybe send the company a cease-and-desist letter, which the company will ignore.

Now, if Joe Smith had applied for and was granted a U.S. Patent, Company X would have to think twice about going to market with a product based on Joe Smith's patent since it would be prohibited from manufacturing or selling a product based on that patent in the largest global market – the U.S. Selling a product based on the U.S. Patent would make Company A liable for a patent infringement lawsuit in U.S. District Court.

And that is why we tell owners of small nation patents to get back to us when they have a U.S. Patent. It is simple a matter of math. Here are the largest economies on our planet:

▪ USA

▪ China

▪ Germany

▪ Japan

▪ India

▪ UK

▪ France

▪ Italy

▪ Canada

▪ Brazil.

If an inventor secures a U.S. Patent, a European Patent (that designates Germany, the U.K., France, and Italy), and a Canadian Patent, he or she would have patent coverage in over half of the 10 largest economies with just three patent filings. Again, it is a question of numbers.

♦ PCT Patent Application: While it is a practical and powerful tool, many inventors do not really understand what a PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) Application actually really is. Let’s start with what it is not. It is NOT immediate global patent protection. We cannot tell you how many inventors write to us about their PCT Patent Applications believing that they have global patent protection!

All a PCT Patent application does is (1.) establish a Priority Date for your patent filing, and (2.) make it easier to file for multiple national patents. It does NOT give you patent protection. You only have patent protection in those countries in which you used your PCT Patent Application to file for a patent in that country. If you do NOT use your PCT Patent Application to file for a patent in Canada (as just one example), you do NOT have patent protection in Canada and any company is free to manufacture and sell a product based on your invention in Canada.

Filing a PCT Patent Application is smart, and it adds value to a patent family or portfolio, but you need to know what it is – and what it is not. A company can buy your patent family that very wisely includes a PCT Patent Application and use it to apply for additional patents in countries where it does business. But get your patent family to market because a PCT Patent Application is only good for 30 months.

* We borrowed the term “Ugly American” from The Ugly American, a best-selling novel (and later movie) of the same name.

Advice for First-Time Inventors

Posted: 8/20/2025

We receive at least one email a day from an inventor claiming to have a “patent” – only to discover after several emails that this inventor actually just has a patent application. In some cases, they have a patent application that they are about to file!

A patent application is NOT a “patent” any more than college application is a college degree! These inventors are not serving themselves well by contacting a patent broker – any patent broker – and commencing the relationship with a bold misstatement on the part of the prospective client! Starting out stating exactly what you have to offer will lead to a much better broker-client relationship.

Every inventor – especially a first-time inventor – has two critical choices to make when he or she files a patent application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) – file a Provisional Patent Application or file a Non-Provisional Patent Application. There is one choice that most definitely serves the needs of a business that will practice the patent, and one choice that serves the needs of the independent inventor who will be seeking to sell or license his or her patented invention.

Let’s first look at the patent application pool. About 75% of all U.S. Patent Applications are filed by businesses, and the Provisional Patent Application was designed for those applicants. A Provisional Patent Application is not published by the Patent Office for 18 months, and that gives a business the opportunity to establish an early Priority Date for the application, fine tune the invention, do some design and engineering work on a product based on the patent, test market the concept, and maybe even get a product to market before the actual patent is granted and mark that product “Patent Pending”. However, a Provisional Patent Application is of NO value to the inventor who hopes to monetize his or her invention!

We cannot tell you how many inventors come to us with a Provisional Patent Application and expect us to take it to market. That is not impossible, but it is also not practical. Every prospective buyer and licensee would need to sign an NDA, and if you have a half-dozen companies signing an NDA, and your patent is leaked, whom do you go after for breaching the NDA? Also, many companies will simply NOT enter into an NDA to limit their down-the-road liabilities.

The smart option for the independent inventor who is not going to build a factory and manufacture products based on his or her patent is to file for a Non-Provisional Patent Application since a Provisional Patent Application offers no significant benefits to the independent inventor who wants to monetize his or her patent. File a Non-Provisional Patent Application and then ask the USPTO to publish it immediately!

An inventor is always, always, always best served by filing a Non-Provisional Patent Application and then requesting that the patent application be published immediately!

Prospective buyers and licensees want to see the complete patent filing, and you simply cannot do that with a Provisional Patent Application. Once your Non-Provisional Patent Application is published, your broker can send prospective buyers and licensees to Google Patents where they can see the Abstract, Claims, figures, narrative, citations, and priority and filing dates.

Many patent attorneys do what we believe is a mistake by suggesting a Provisional Patent Application to first-time inventors, but that is because the patent attorney’s job is to get the patent granted, not monetize the patent. It is always in the best interests of the inventor to file a Non-Provisional Patent Application … and … request that the USPTO publish it immediately!

What do you do if you are an inventor with a Provisional Patent Application sitting at the Patent Office collecting digital dust?

1. Immediately convert it to a Non-Provisional Patent Application.

2. Request that the USPTO publish your Non-Provisional Patent Application.

3. Once your patent application is published, contact IPOfferings at [email protected].

OTT Is Hotter than Ever!

Posted: 8/5/2025

Regular readers of this delightfully witty and informative column know what OTT is. But, if you are a reader and you forgot; or you are new to IP MarketPlace, or you just want the latest on the world of OTT, here it is. OTT (Over the Top) is – in the simplest terms possible – the delivery of audio and video content over the Internet as opposed to via broadcast or broadband (what we used to call “cable”). It is called “over the top” because it skips “over” all the regular distribution channels for this content.

Since KDKA went on the air November 2, 1920, everyone on the face of the earth has received news, music, sports, drama and advertising via radio waves. Just eight years later, a one-act play, “The Queen’s Messenger,” was broadcast by RCA over W2XBS September 11, 1928. Since then, virtually everyone on the face of the earth has viewed drama, comedy, news, sports, movies, and commercials via television.

In 1940, John Walson was running an appliance store in Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania. He had a problem selling television sets because the town was in a valley, so TV reception was very poor. He put a tower on the highest mountain, captured the TV signals from the Philadelphia stations, ran a cable down into the village, and provided the first cable TV service. Since then, hundreds of millions – in this case, not everyone on the face of the earth – have received their television signal not from an antenna on the roof or rabbit ears on the TV set, but from a local cable TV vendor.

A book could be written about why the cable TV companies got into the Internet service business instead of the local telephone companies – who were all in business with a loyal customer base 100 years ahead of the local cable companies – but they did. Today, broadcast and cable TV is slowing losing customers to one form or another of OTT content delivery. The irony of it all is that the OTT content is coming in on the Internet service provided by the cable TV companies!

Cable TV companies are enormously profitable. That’s how Comcast managed to buy NBC. Cable companies sell bundles of TV networks, so consumers end up paying for many channels they never view. And the cable companies get to drop in their own ads over the ads of the original provider of the programming. We have only the greatest respect for effective marketing, and the cable TV companies are great marketers. In fact, it took OTT this long to catch on in large part because the fragmented OTT vendors did not have the marketing tools, marketing savvy, and marketing umph of the cable TV companies. Never underestimate umph!

Netflix was the first company to crack the cable monopoly. Netflix licensed older programming from the TV networks, then veered around and “over” the cable guys to reach customers via the Internet. Hulu soon followed, and the rest, as they say, is history.

One result is that we have a section for OTT patents in our Patent MarketPlace and we recently licensed an OTT patent family. Many marketing and technical challenges are out there for the OTT crowd, but new patents continue to pop up to address improvement of the delivery of audio and video content.

The future: OTT is here to stay, but so is cable. It is likely that programming revenue from cable will decline as more consumers shift to OTT content. How will cable TV operators make up the difference? They will have to charge more for the Internet service on which the OTT content flows into the homes and businesses of their customers!

From the Sheaves to the Threshing Floor

Posted: 7/9/2025

There are references throughout the Old Testament to the threshing floor. Wheat was cut in the field and collected into sheaves, which were brought to the threshing floor. The stalks of wheat were flailed, causing the wheat buds to drop off. The useless part of the wheat plant, the “chaff” was burned as it had no use even as fertilizer or mulch. The wheat buds where then ground into wheat for bread. The whole process “separated the wheat from the chaff” and from that winnowing process has been drawn many lessons.

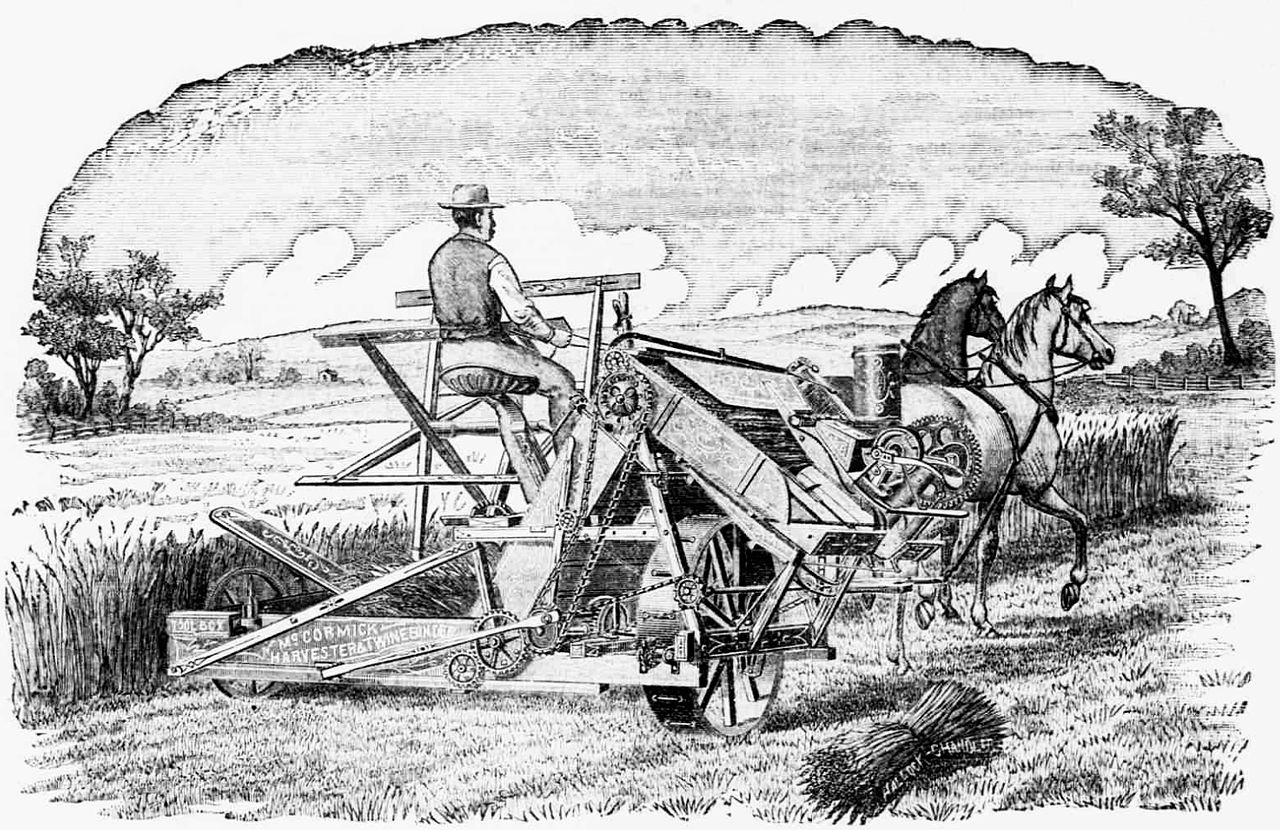

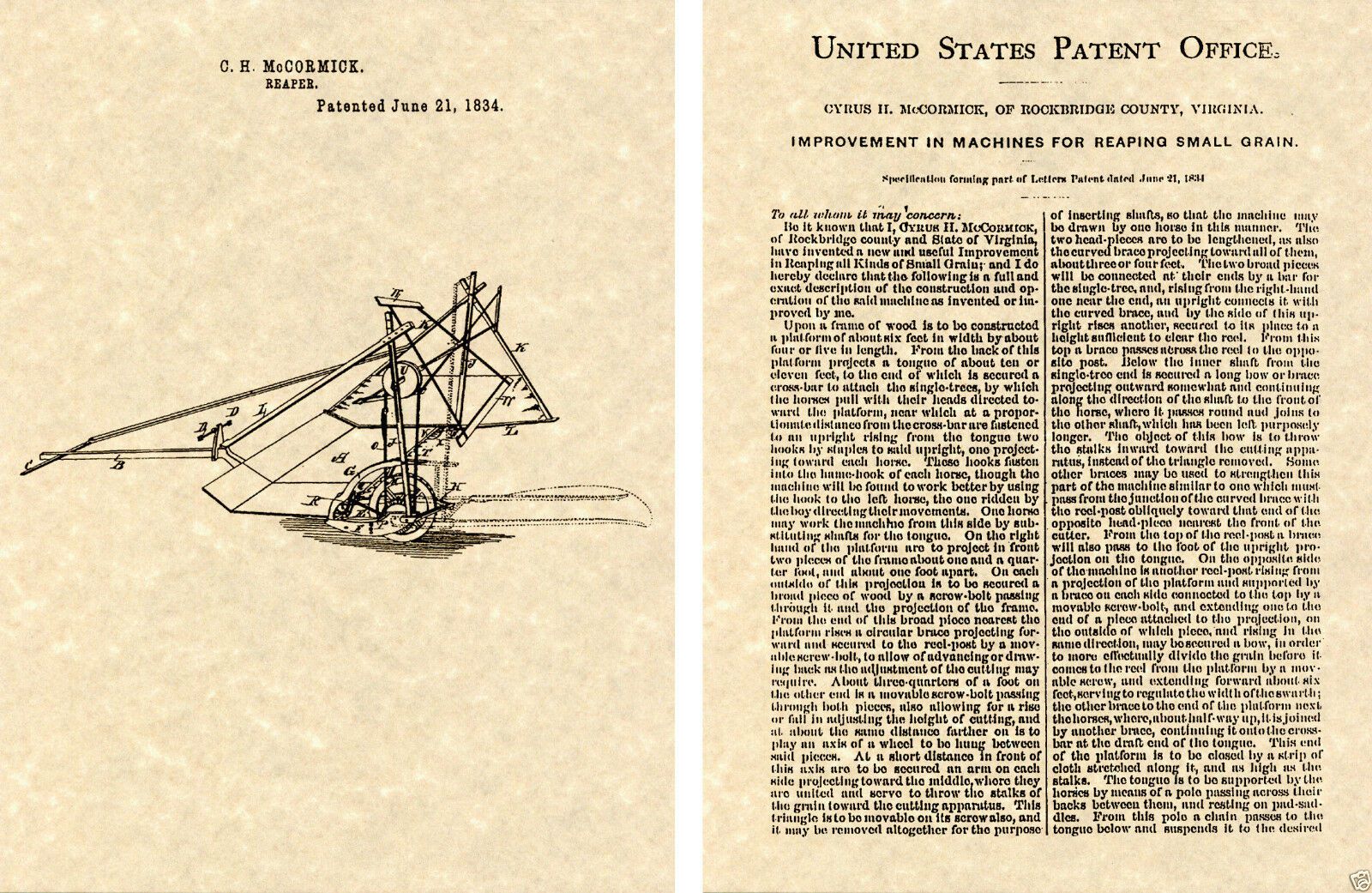

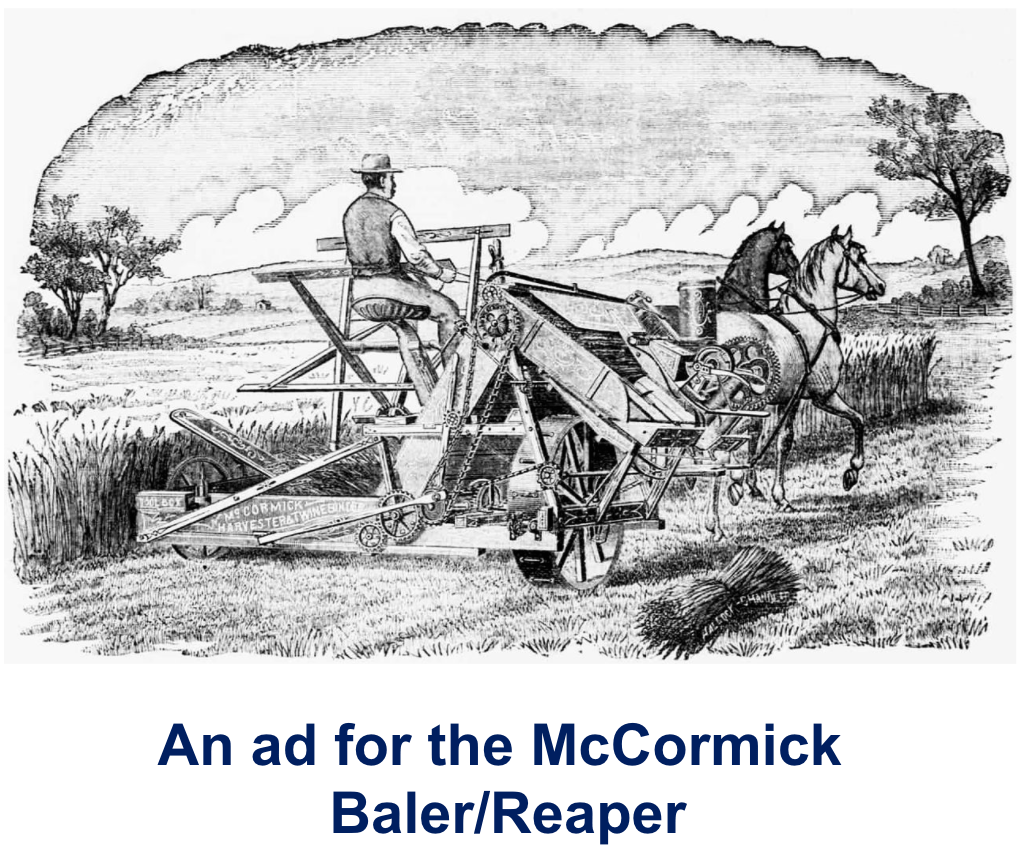

That was the process until only about 200 years ago. In 1831, Cyrus McCormick introduced his Reaper, a machine that would cut the wheat and collect it into sheaves, but he did not apply for a patent until 1834. It took him a few years to set up production, and by 1842 he had sold seven reapers. He sold 29 Reapers in 1843 and 50 in 1844. In 1847, he moved his factory to Chicago and exhibited his Reaper at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851.

When McCormick went to renew his patent in 1848, he was informed by the Patent Bureau that since one Obed Hussey had applied for a patent for a Reaper back in 1833, McCormick’s Reaper Patent would not be renewed and he was to pay royalties to Mr. Hussey! Undeterred, McCormick charged ahead, manufactured reapers that were sold all over the world, and made a fortune. He married his secretary, and had seven sons, one of whom married a daughter of John D. Rockefeller.

Now that grains could be mechanically cut and gathered into sheaves, there was still the issue of separating the wheat from the chaff. The two processes – reaping (or harvesting the grain) and threshing or thrashing the harvested grain to separate the wheat buds – needed to be merged into one operation, and that was done by Hiram Moore and John Hassall who received a patent in 1836 for a “Machine for Mowing, Threshing and Winnowing Grain.”

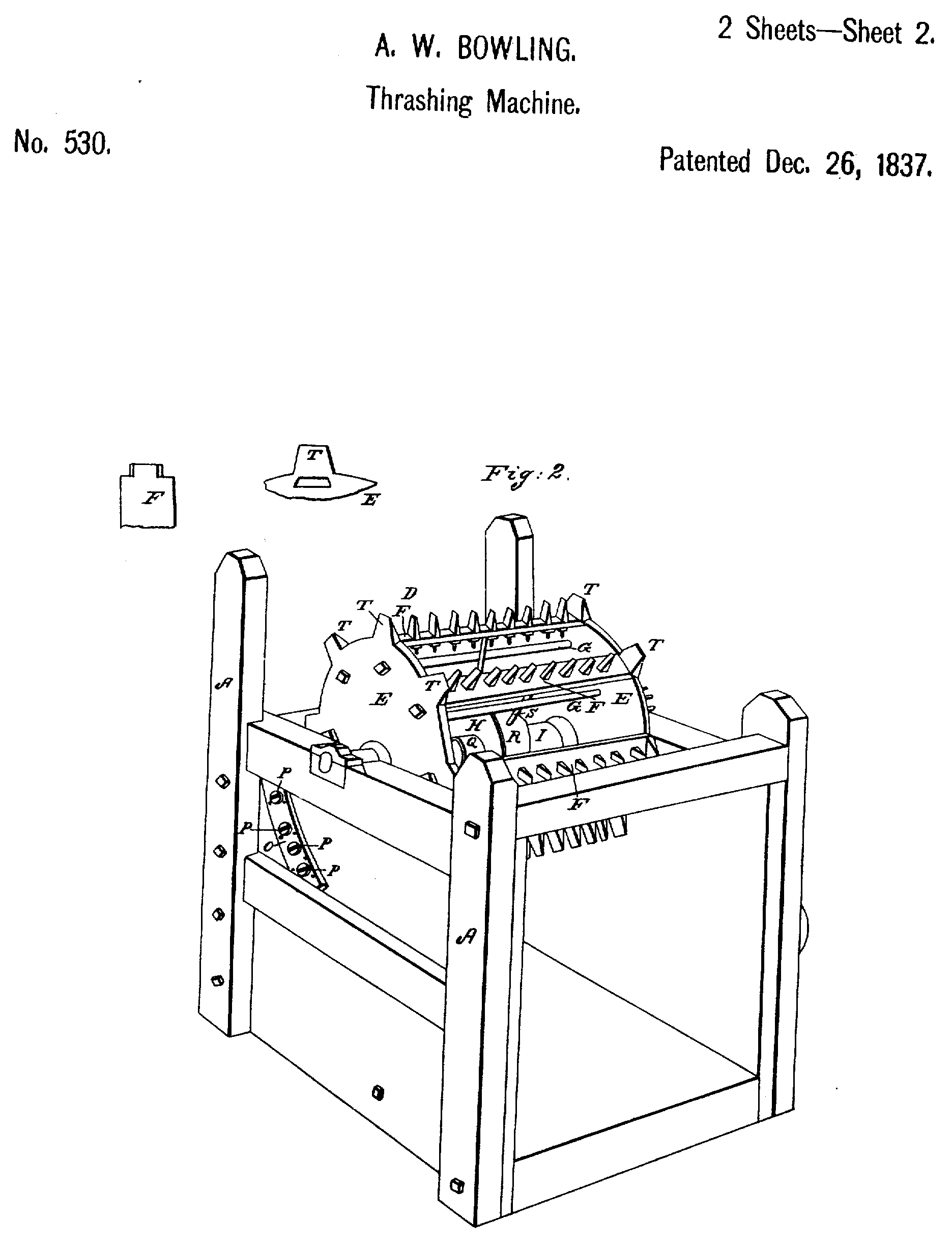

On December 26, 1837, A.W. Bowling received U.S. Patent No. 530 for a “Thrashing Machine,” and just three days later, John and Hiram Pitts received U.S. Patent No. 542 for a “Machine for Thrashing and Separating Grain” on December 29!

Somehow “threshing” was now “thrashing,” and both inventions were based on a drum into which the sheaves were fed, and as the drum turned, teeth in the drum broke up the stalks of wheat so the wheat buds would drop out the bottom. These units never really caught on since a combined unit to both reap the wheat from the field, and thresh and winnow out the wheat buds, just made more sense. From this concept came the combine harvester of today.

What Ever Happened to Fuel Cells?

Posted: 7/9/2025

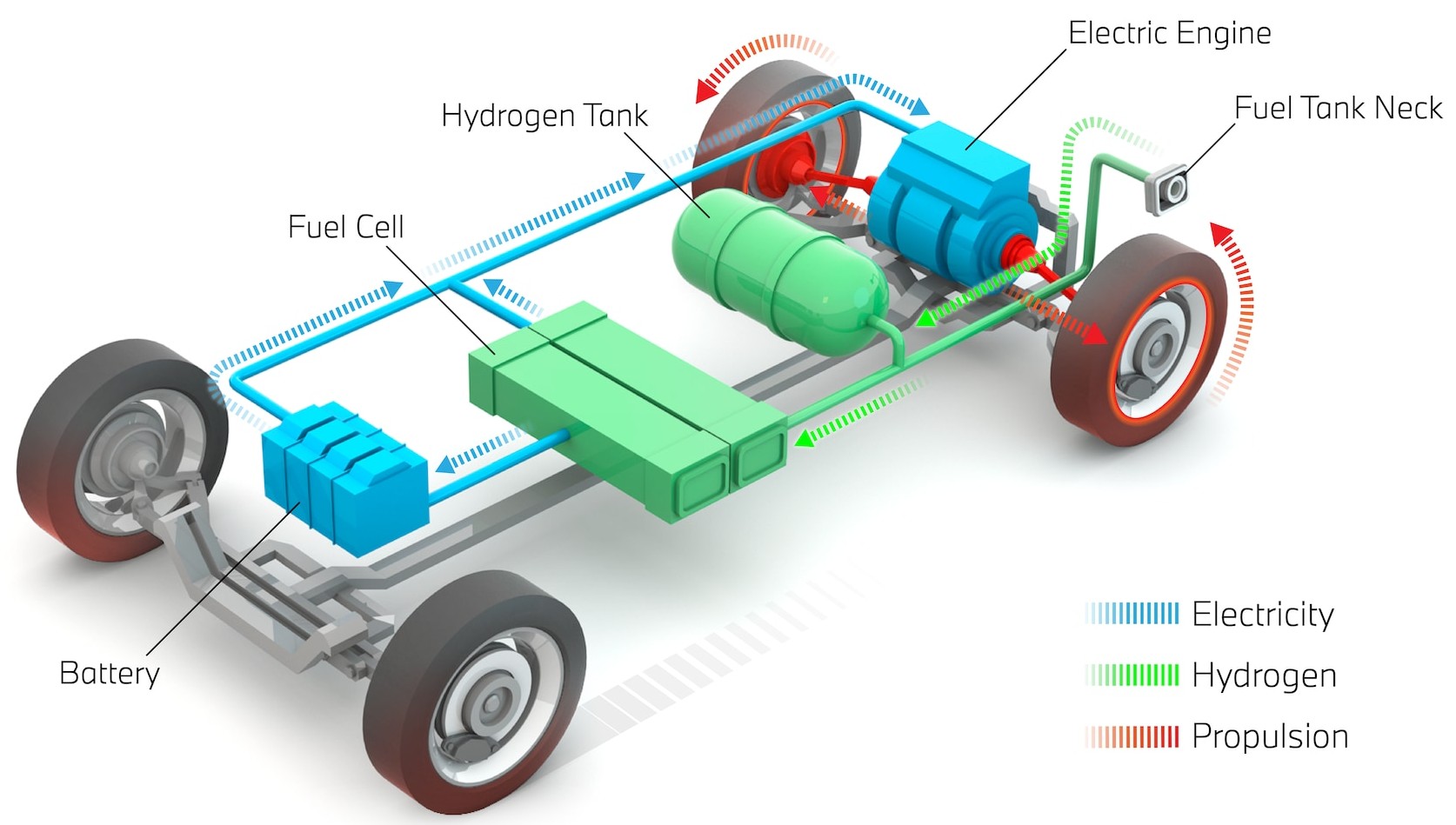

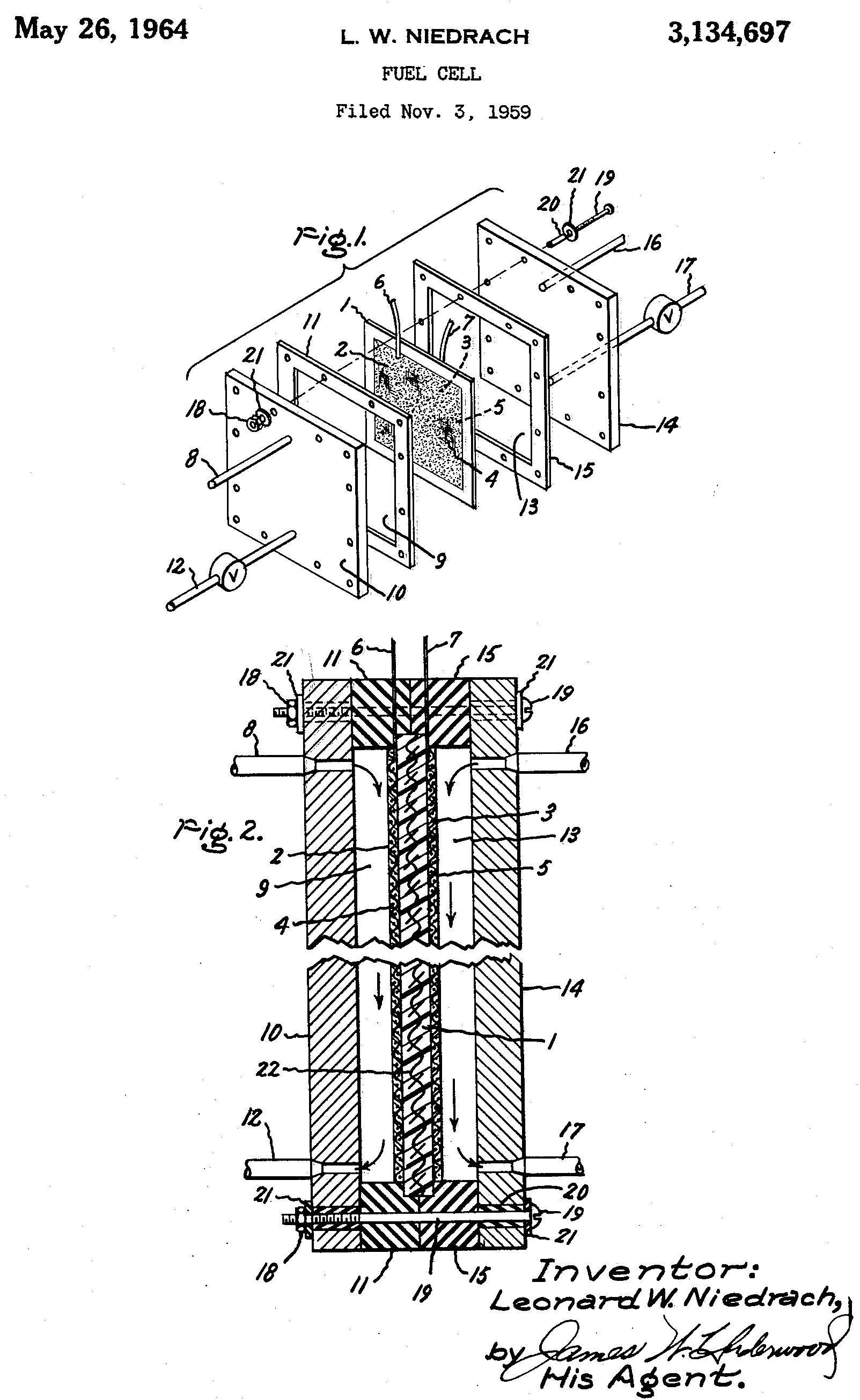

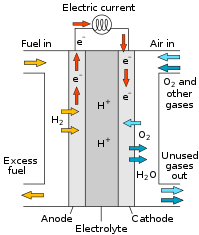

Fuel cell-powered automobiles burst onto the scene a decade or so, but they never caught on. A fuel cell – for those of your not in the know – merges hydrogen and oxygen to form water vapor, and in so doing captures a stream of hydrogen electrons as they make there way to meet their soon-to-be oxygen mates. And a stream of electrons is what we call “electricity”!

At first glance, fuel cells appear to be the ideal source of power. They are clean, they use no fossil fuels, and they discharge water vapor. They also have NO moving parts! So why did they never catch on.

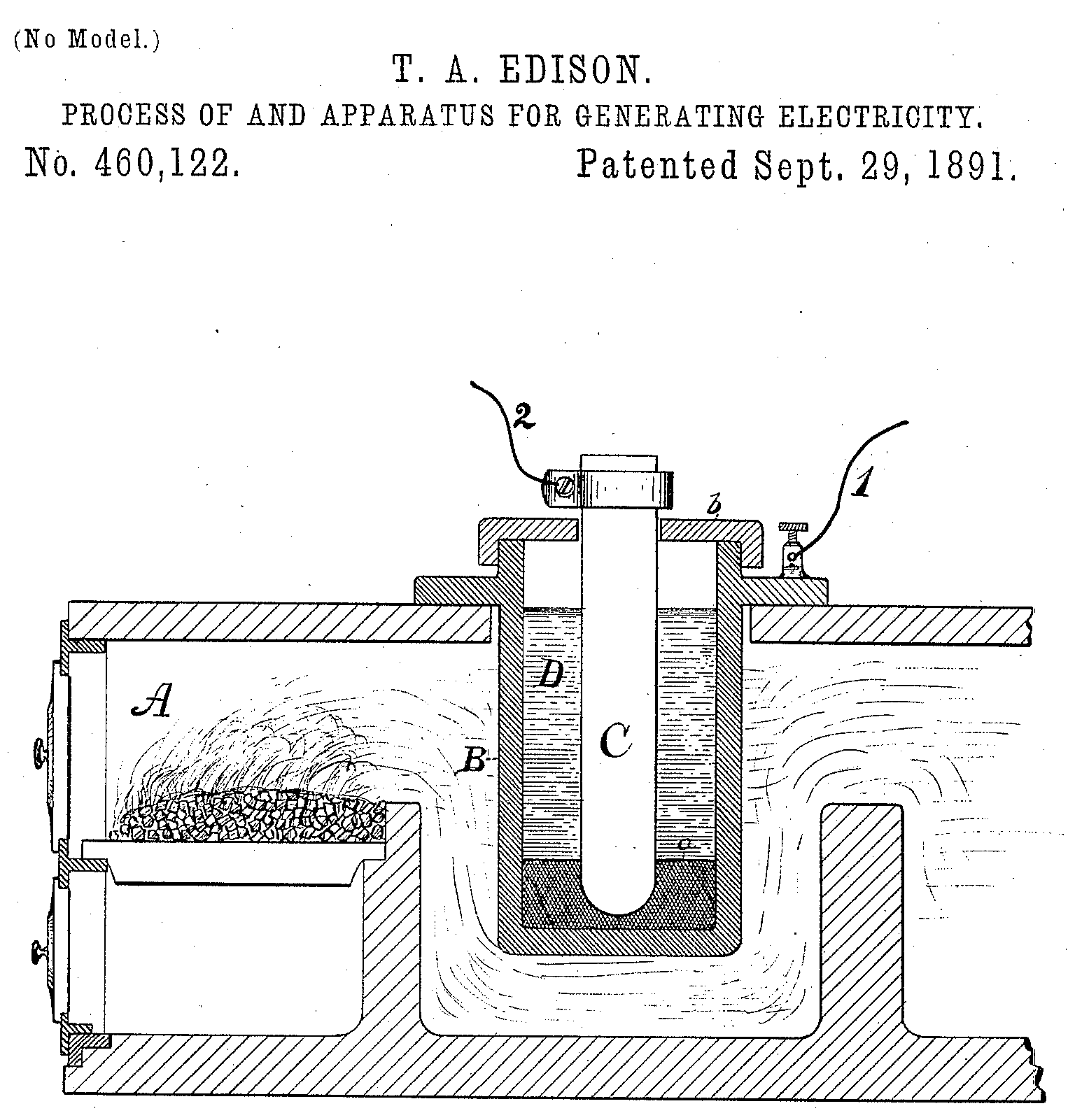

To start with, fuel cells are not new. Sir William Grove is credited with inventing the fuel cell way back in 1839. None other than one Thomas A. Edison jumped on the idea and was granted U.S. Patent No. 460,122 for a “Process for and Apparatus for Generating Electricity” in 1891, but Edison never commercialized the technology.

No one found a practical application for the technology until NASA came along in the second half of the 20th century to use fuel cells to power their space craft. NASA could carry hydrogen and oxygen into space and use a fuel cell to produce clean electricity for the spaceship’s electronics. Fuel cells were used in both the Gemini and Apollo space missions, and the water vapor produced by the fuel cells was condensed and used for drinking water for the astronauts.

In the early years of this century, several companies sprang up to manufacture fuel cells including Ballard Power Systems, Plug Power, and FuelCell Energy. Most of the car companies developed fuel cell-powered vehicles to test the concept. At one point, Jeep had 40 fuel-cell powered Grand Cherokees being driven around Michigan by Chrysler employees.

But fuel cell-powered cars just never caught on for two reasons:

1. Hydrogen is Expensive: In order to have the hydrogen to merge with oxygen, the hydrogen has to be extracted from something. Hydrogen is an element, so it cannot be produced from other substances. It is most often extracted from methane, but methane and the process of extracting the hydrogen are both expensive.

2. No Infrastructure: To support large numbers of fuel cell-powered autos, we will need hydrogen fueling stations, but with without a significant number of fuel cell-powered cars on the road, no company is prepared to make an investment in them.

Why Most Patent Transactions Are Confidential

Posted: 6/25/2025

It has become a common practice in recent years for buyers of patent to insist that the transaction be confidential. They do this for several reasons.

♦ Avoid Unsolicited Contact: When a company announces that it has acquired a patent, it runs the risk of selling off a tidal wave of inventors contacting the company about their inventions. One IP Director told us that after her company released news of a patent acquisition, she was inundated with emails and telephone calls from inventors – many with inventions that were totally unrelated to her employer’s business! Some inventors even showed up in person while others shipped her prototypes.

♦ Not the Image the Buyer Wants to Promote: Most businesses what their customers to think that their management team is brilliant. They want their customers – and competitors – to believe that every product they sell was the result of in-house brilliance by their R&D staff, or engineering team, or CTO. Admitting that a company has acquired a patent from an inventor or another business sends the message that the company is not, in fact, as intellectually gifted that they would like their customers to think.

♦ Give Away Plans to Competitors: When a company announces that it has acquired a patent, it is essentially revealing its product strategy to its competitors. By acquiring a patented technology in confidence, and quietly developing a new product based on that technology, the company can spring the new product on its customer base and catch its competitor’s totally off guard.

So, for these reasons and a few others, most companies that acquire patents require total confidence from both the seller of the patent and the broker that negotiated the transaction. This is built into the Patent Purchase Agreement so it is a condition of the sale! In most Patent Purchase Agreements today, both the seller and the broker are not even permitted to make any mention – in writing or orally – about the transaction.

♦ What About the Patent Office? When a patent changes hands, the transaction is recorded at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. So, you ask, all a curious person has to do is look up the transaction at the Assignments section of their website. True, but you need to know the patent number of the patent that was acquired. Or you have to do a reverse look-up of new patent assignees to determine if a specific company has acquired patents. To protect themselves from searches such as these, many companies set up an LLC to hold their patents.

The bottom line is that when you sell your patent, do not look for bragging rights about who you sold your patent to and for how much. And do not be surprised if the patent broker you are thinking about representing you cannot provide a list of patent sales they consummated for their clients.

Trying to Sell a Just-Filed Patent Application

Posted: 6/25/2025

We are contacted just about every day by an inventor who just filed his or her patent application, and now they want to sell or license it. The reality is that attempting sell a Provisional Patent Application is just not a practical undertaking.

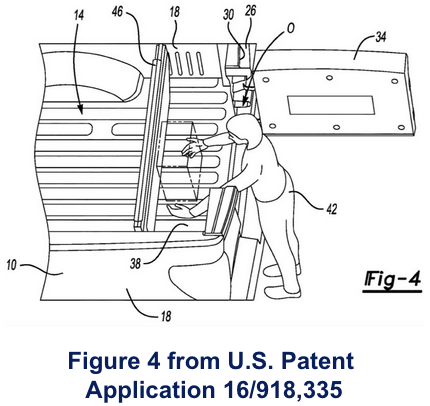

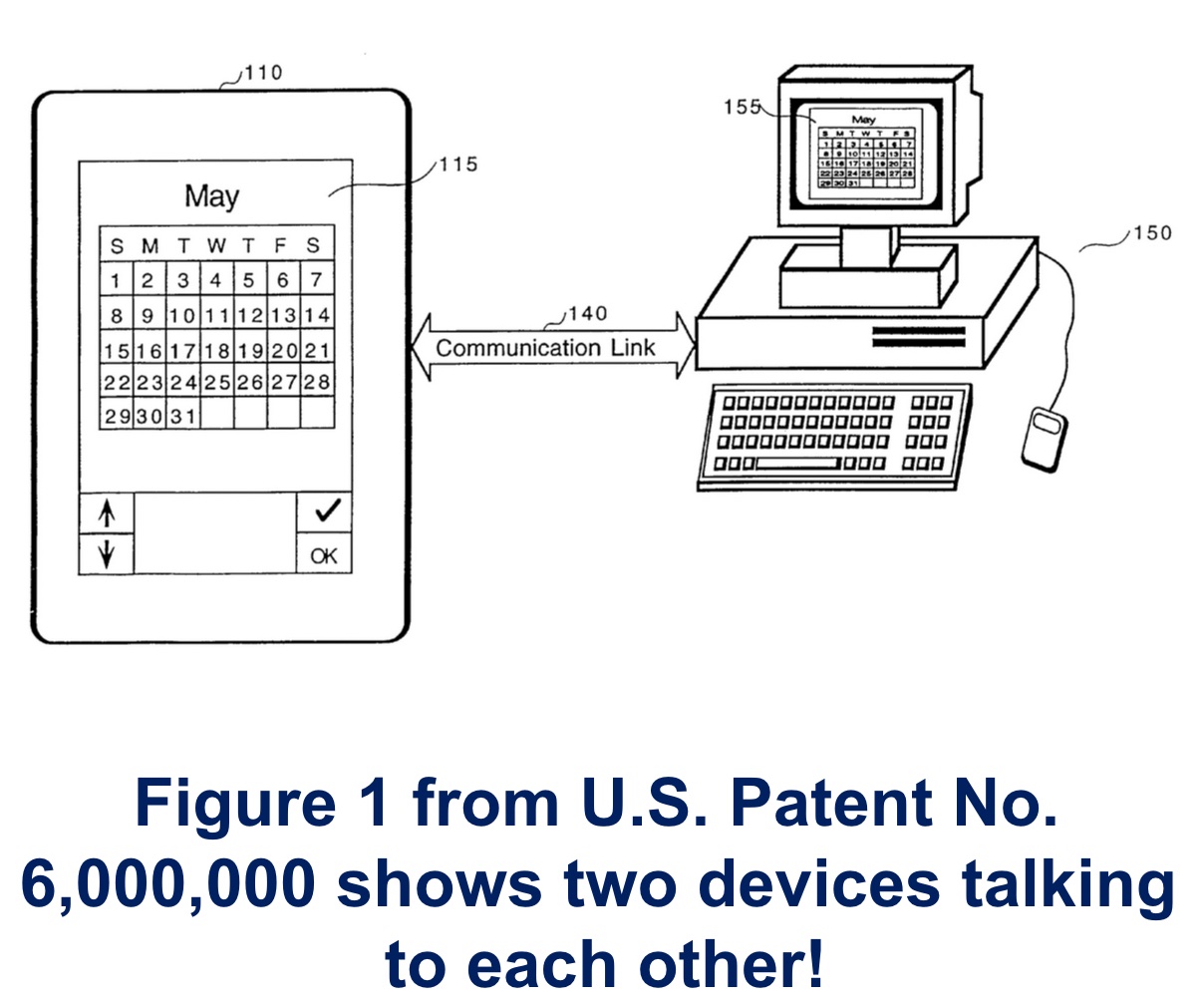

When we take a patent (or portfolio) to market, we can send prospective buyers or licensees to Google Patents where they can see the entire patent filing. We prefer Google Patents over the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) website because it includes more data. When we send a prospective buyer or licensee to Google Patents, he or she can see the abstract, claims, narrative, and artwork of the patent. Google Patents also provides the Priority Date and Application Date, when the patent was granted, and when it expires. Google Patents also includes any Prior Art as well as Backward and Forward Citations. It is most comprehensive and informative, and easy to navigate. Bravo Google. And it is free.

Let’s go back one step from there. If we are representing a published patent application (it will have an 11-digit number of which the first four digits are the year the application was published), Google Patents shows everything a buyer or licensee would want to know about the published patent application, including everything that is shown at the listing of a granted patent except, of course, the date the patent was granted since that event has not yet occurred. Visitors to a published patent application filing realize that what they see at Google Patents may not be the eventual granted patent. Some claims, for example, could be rejected by the patent examiner or modified by the applicant.

OK. Let’s go back in time one more step to this freshly filed patent application. While a granted patent is a public document, and a published patent application is a public document, a recently filed Provisional Patent Application is NOT a public document! An interested buyer or licensee cannot go to the USPTO website or Google Patents or anywhere else to see the actual patent application filing! And therein – to quote the Bard – lies the rub.

When an inventor or business or university or anyone else files a patent application, it is kept private by the Patent Office for 18 months. So, during those 18 months, we cannot send a prospective buyer a link to go and see the patent application. And sending out what is in the unpublished patent application to a prospective buyer or licensee is…well…messy to say the least. So, we do not represent patent applications that have not yet been published!

However, an inventor can request that his or her or its patent application be published immediately. The inventor can file a 1129 Request for Early Publication [R-11.2013]. The patent application will be assigned an 11-digit number and be published – usually with a few weeks. Once it is published, and is a public document, it is now practical for us to take it to market.

For more information about this, visit the Advice for the First-Time Inventor page at our website.

Who Really Invented Voicemail?

Posted: 6/10/2025

Jimmy Carter was President, the Iranians were holding 52 American hostages, Dallas was the top-rated TV show, the Olds Cutlass was the best-selling vehicle, and the world was introduced to voicemail. But being the patent guys we are, we have to ask ourselves: Who invented this technology that has now been such an essential element in our lives for over 45 years?

Voicemail was launched by Televoice International that also coined the term “voicemail” (no argument about that). The company later changed its name to Voicemail International and eventually to just VMI. However, we always look at things from a patent perspective, so we had to ask ourselves not who introduced voicemail to the known world, but who actually invented voicemail? Credit is typically given to Gordon Matthews who has been known for the last four decades as the “father of voicemail,” but there were actually a few voicemail-related patents that preceded his.

U.S. Patent No. 4,124,773 - Audio Storage and Distribution System: This patent was granted November 11, 1978, two years before any voicemail products were introduced. The inventor was Robin Elkins and he eventually sold his patent to VMI. Here is the abstract: This invention relates to an electronic system and a method for storing and distributing audio signals over existing communication lines. The system comprises a compressor for compressing in a predetermined manner the waveform amplitude of an input analog signal, thereby forming a compressed analog signal. The compressed analog signal is then converted into a digital signal by an analog to digital converter. A digital interface subsystem stores and retrieves selected ones of the digital signals for transmission over a communications line. At a remote end of the communications line the digital signal is converted back to its analog compressed signal representation by a digital to analog converter. The compressed analog signal is then expanded in a manner complementary to the compressor operation, thus reconstructing the analog signal. A selector generator is provided at the remote end of the communications line for generating a command signal over the communications line to command the digital interface subsystem to select the desired one of the stored digital signals. The patent currently has 66 Forward Citations.

U.S. Patent No. 4,260,854 - Rapid Simultaneous Multiple Access Information Storage and Retrieval System: This patent was granted April 4, 1981, one year after Televoice introduced its voicemail product. It introduces the concept of “…multiple simultaneous…audio dictation…” The inventors were Gerald Kolodny and Paul Hughes, and the patent was assigned to Sudbury Systems. Here is the abstract: Rapid simultaneous multiple access information storage and retrieval system including multiple simultaneously available audio dictation inputs and multiple simultaneously available audio outputs, an array of magnetic recording and playback instruments, and a controller operating under computer command for multiplexing the interchange of audio signals between inputs and outputs on the one hand and the magnetic recorder storage means on the other and at the same time for generating control signals to and from the input and output terminals. This patent has 51 Forward Citations.

U.S. Patent No. 4,371,752 - Electronic Audio Communication System: This patent was granted February 2, 1983, three years after Televoice introduced voicemail. It included additional features over the first two voicemail patents, such as the ability to forward voicemail messages. The inventors where the previously mentioned Gordon Matthews plus Thomas Tansil and Michael Fannin, and the patent was assigned to ECS Telecommunications, then sold to Glenayre Electronics. Here is the abstract: An advanced electronic telecommunication system is provided for the deposit, storage and delivery of audio messages. A Voice Message System interconnects multiple private branch exchanges of a subscriber with a central telephone office. Individual subscriber users may access the Voice Message System through ON NET telephones or OFF NET telephones. The Voice Message System includes an administrative subsystem, call processor subsystem and a data storage subsystem. The Voice Message System enables the user to deposit a message in data storage subsystem for automatic delivery to other addresses connected to the system. The Voice Message System also enables a user to access the system to determine if any messages have been in the data storage subsystem for him. Pre-recorded instructional messages are deposited in the data storage subsystem for instructing a user on his progress in using the system. A Universal Control Board is a programmable electronic digital signal processing means for controlling certain functions of the administrative subsystem, call processor subsystem and data storage subsystem. This patent has a whopping 242 Forward Citations, making it a far more foundational patent than the others.

So who really, really invented voicemail? We like Elkins.

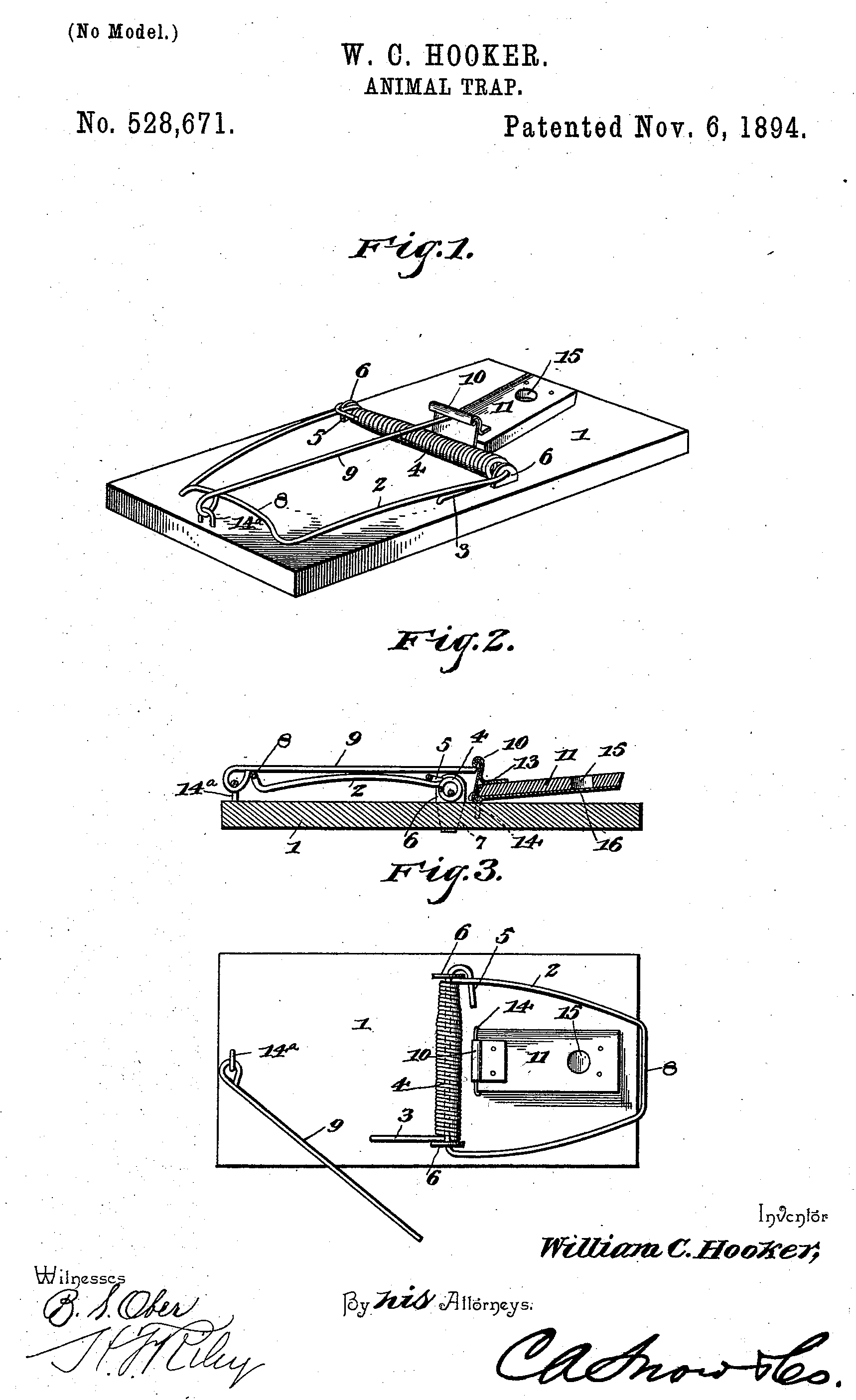

Build a Better Mousetrap....

Posted: 6/10/2025

We've all heard this adage from Ralph Waldo Emerson a few thousand times: Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door. Well, we thought it was about time we found out who actually did, and it was one William C. Hooker. Mr. Hooker is widely recognized as the man who invented the classic, spring-loaded mousetrap, and that is supported by U.S. Patent No. 528,671 granted November 6, 1894 for an "Animal-Trap." He called it an "animal" trap because in the abstract the invention is described as catching "mice and rats." Why the hyphen? We cannot tell. In the application, no prior art was cited. And, we must assume, none was found by the patent examiner who signed off on the patent.

Taking the "better" concept seriously, Bill followed up with U.S. Patents 580,694 in 1897, 665,906 and 665,907 in 1901, 717,002 in 1902 and 744,343 in 1903. Each patent was an improvement on the previous "Animal-Trap" except it still had that pesky hyphen.

Bill Hooker's genius is still recognized today. In 1981, Sterling Drug was issued U.S. Patent No. 4306,359 for "Animal Traps." We see little significant improvement in the '359 patent over the original '671 patent other than they got rid of the hyphen. And as recently as 2006, one John Peters was issued U.S. Patent No. 7,117,631 for a "Microencapsulated animal trap bait and method of luring animals to traps with microencapsulated bait" that looks a lot like Hooker's 1894 version. Peter’s latest patent has 26 Forward Citations. The search for that better mousetrap continues to this day.

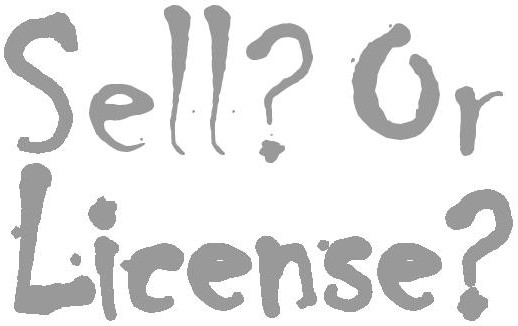

Licensing versus Selling – and Licensing versus Buying – a Patent

Posted: 5/27/2025

We are asked all the time by both patent owners looking to monetize their patents and businesses looking to acquire new technology the benefits of licensing versus selling or buying a patent. So here is our 2 cents.

Most companies prefer to own a patent. They prefer to pay cash, own the patent, and carry it on their books as an asset. They can practice the patent, and assert it against any and all infringers. They may have strategic partners to which they might license or cross-license the patent. But all things being equal, if they have the cash, businesses prefer to buy and own the patent.

If a company does not have the cash to buy a patent outright, it will consider licensing it. This applies to start-up businesses, or businesses that have faced a downturn and are looking at new technologies to make a turnaround. The problems with licensing a patent – especially if it is a non-exclusive license – is that the licensor can license the patent to all of the first licensee’s competitors, wiping out any competitive advantage that the first licensee had. When a company licenses a patent, there is also the issue of computing each quarter the sales that are subject to the royalty. For example, if it is a U.S. Patent, no royalty is due on export sales, so they have to be backed out in order to compute the royalties that are due.

For the assignee, the problem with licensing is that the licensee may or may not be successful with a product line based on the licensed patent. If Company A licenses a patent, and then never generates any significant sales from products based on the licensed patent – for whatever reason – the licensor takes a hit. But if the product takes off, the licensor can do very well! Selling the patent is low risk/low return. Licensing the patent is high risk/high return.

There is also the issue of enforcement. If a patent is licensed, and the patent is infringed, the licensee often does not have standing to bring an action against the infringer, and the licensor – often an individual and the inventor – does not have the resources to pursue the infringer. So the licensee ends up with a competitor that is infringing the licensed patent and not paying a royalty.

There is no simple response to the question of whether it is better to sell or license, or buy or license, a patent. There are a number of factors that have to be considered. That is why IPOfferings always takes a broad “monetization” approach when we take on a patent as a brokerage project.

There is a very good book that covers patent licensing. “Essentials of Licensing Intellectual Property” is available at Amazon for about $25.00 and it covers most comprehensively what both a licensor and licensee needs to know.

If you are a business executive torn between buying or licensing a patent – or an inventor not sure about selling or licensing your patent – we can help you determine what the key factors are that need to be taken into consideration so you can make the best decision. Because, hey, that’s what we do!

Mitigating Threats to the Patent System

Posted: 4/30/2025

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has implemented the Patent Fraud Detection and Mitigation Working Group. The purpose of this Working Group is to protect the integrity of the U.S. patent system. The Working Group will detect and mitigate threats to the patent system by:

- Identifying and reviewing potential misrepresentations to the USPTO, and when appropriate using the administrative sanctions process to address misrepresentations, including false signatures

- Addressing mistakes in fee certifications and assertions

- Monitoring suspicious filings

- Preventing non-practitioners from engaging in the unauthorized practice of law

- Serving as the main point of contact within the USPTO for reporting potential threats to the patent system

- Adapting USPTO systems and processes to respond to new schemes

Like any organization, the USPTO is faced with fraudulent activities. These include:

- Falsified signatures

- False claims of discounted fee status

- Filing of “spurious” patent applications by bad-faith applicants who use technology to electronically file high volumes of patent applications with NO intent to fully prosecute those applications

- Unauthorized representation before the USPTO

Since its founding just a few months ago, this group has produced significant and impressive results! The group identified 3,900 falsified signatures going back to June 2023 and it terminated 3,300 applications going back to October 2024. More than 2,200 fee deficiency notices were mailed in response to false micro entity status certifications, and more than $1.8 million in fee deficiency notices were collected!

Unpracticed Patents Can Become Money in the Bank

Posted: 4/9/2025

We are often contacted by businesses to ask if we can do something with the patents they are not practicing, and the answer is often “Yes” – but’s let’s start with how a company ends up with patents it is not practicing.

A smart business automatically files for patent protection on any new technology its engineering staff or Research & Development team, or marketing department, or sale force, or Joe from the loading dock comes up with. We actually represented a patent a few years back that was inspired by one of the company’s warehouse employees. But he might not have been Joe.

So, as a wise precaution – and since it does not incur any risks or great costs for the business – smart companies file for patents on any new technology that might have potential for the company.

But then the world happens.

• A business’s focus changes, so it does not ever develop a product based on a patent.

• A new technology comes along that obsoletes the patented technology.

• It may be determined that the market for a product based on a patent is just not big enough to justify the investment.

• A product line based on a patented technology may not have synergy with the enterprise’s other product lines, drawing corporate resources away from the company’s central mission.

• The investment required to bring a new product to market may be too great for a company to be willing to put funding into it.

• A business can be acquired, and the new parent company is moving in a different direction.

• A business unit may be divested or closed, but its patents remain in the parent company.

These are just a few of the reasons why a business may file for and end up with a patent or a patent portfolio, but end up not using the patented technology.

IP Offerings developed the concept of “Patent Triage.” Just has hospital emergency rooms evaluate each incoming patient to determine who needs to be seen immediately and who can wait – a process call “triage” – a business’s patents can be put to scrutiny to determine if they are or are not being practiced. And what alternatives there are to consider.

When a company has its patents put through Patent Triage, each patent will end up in one of five sectors of the Patent Triage pie:

♦ Core: These are patents that are core to the business’s mission and are being practiced. They should be kept and maintained until the day they expire.

♦ Assertion: If a patent is being infringed, an assertion campaign could generate significant income.

♦ Non-Core: These patents are not being practiced, but for any number of reasons it makes sense to retain them. They might have potential a few years out, or they may cover technology that a competitor could use.

♦ Divestiture: These are patents that are not currently – and not likely to be in the future – relevant to the core missions of the business. They should be turned over to a patent broker as they could generate substantial cash. What is the old expression? One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

♦ Licensing: A business might have patents it is practicing, but other non-competing businesses might benefit from them, and licensing those patents could generate a nice revenue stream.

If your business has over 100 patents, it would make a lot of sense to contact IPOfferings and investigate a Patent Triage review of them.

Soon-to-Be New Director for the Patent Office

Posted: 3/26/2025

A new, in-coming U.S. President has to make about 4,000 appointments, and roughly 1,200 of them require Senate approval. That means a Senate Committee has to hold a hearing and interview the nominee, and then either turn down the candidate or send him or her to the full Senate for confirmation. Not surprising, the cabinet heads (Secretary of State, Attorney-General, EPA Administrator, etc.) come first, so it has taken a while for the incoming administration to work its way down to the Patent Office.

On March 11, the Trump Administration nominated John Squires to be the next Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and Under-Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property. Squires is the chairman of the Emerging Companies and IP practice at the Dilworth Paxson law firm. Prior to that he was Chief IP Counsel at Goldman Sachs from 2000 to 2008. He previously practiced law at Gibson Dunn & Crutcher and Perkins Coie. Squires is generally considered pro-patent.

When a new president takes office, all appointees from the previous administration resign. The Patent Office Director under the Biden Administration, Kathi Vidal, left office back on January 20. Each in-coming administration appoints acting Secretaries, Administrators, and Directors. Since January 20, the USPTO has been run by Coke Morgan Stewart. She is known to be a strong believer in the U.S. patent system and patent rights in general, and she has served in several high-level positions in the Patent Office. There were several recommendations to make her new permanent director, but Squires won the nod.

When a new President is elected, he sets up a Transition Team, and it is this group’s job to come up with candidates to fill these 4,000 appointments. The team brings two or three candidates to the President, and he makes the final decision – or so it is supposed to go. The Transition Team usually starts with White House staff positions such as Chief of Staff and Press Secretary that do NOT required Senate approval. They then move to the Cabinet Secretaries that do require Senate approval. The first cabinet Secretary to be approved by the Senate was Marco Rubio for Secretary of State by a 99-0 vote. There are still about 380 appointments to be made that require Senate approval.

Article II Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution is known as the “Advice and Consent’ clause. He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

The brilliance of the Founding Fathers continues to amaze us!

There Are Two Broad Strategies for Monetizing a Patent – Part II

Posted: 3/12/2025

In our last installment, we shared some advice regarding selling or licensing a patent versus asserting the patent against its infringers. And we emphasized that most patents are NOT infringed, so that leaves the patent owner with an uninfringed patent only one monetization option – find a patent broker to represent him or her and sell or license the patent. A business with a patent it is not practicing has the same two options, but only if the patent is being infringed.

We defined infringement and included our recommendation that a patent owner – be it an individual or a business – invest in an Initial Infringement Analysis to clearly determine if his or her or its patent is truly infringed and by what products. An Initial Infringement Analysis is a study performed by a team of patent professionals that specifically identifies products that are infringing a patent and ranks them in order of viability as assertion properties. That ranking is very important because a product might be infringing your patent, but it might not be a viable candidate for patent assertion.

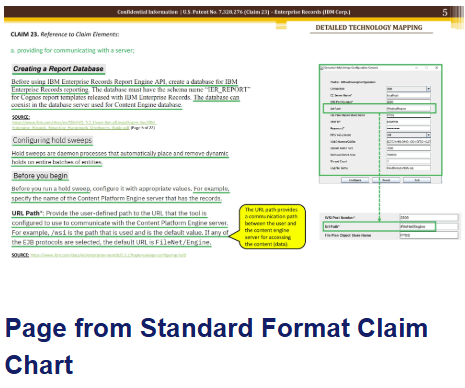

Based on the results of the Initial Infringement Analysis, the patent owner can identify the most viable assertion candidates, and order a Claim Chart for each. A Claim Chart is a document that breaks up a claim from a patent into its key elements, and then documents infringement of each element of the claim. A Claim Chart is the “smoking gun” of patent litigation that clinches the case for the patent owner.

We like the old expression “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire” because it applies very directly to the possible infringement of a patent. The most obvious indicator that a patent has been infringed is if the patent has a large number of Forward Citations. When a patent application is filed, it includes Prior Art – any existing documents (including prior patent filings) that are foundational to the technology in the patent application. A Forward Citation is the opposite of Prior Art. Rather than a patent that is cited by the applicant, it is a patent application that cites your patent as being foundational to its technology.

When a patent has over 100 Forward Citations, that means that all those companies have products covered by technology of which your patent is foundational. It is not uncommon for companies to file for patents that cite a previous patent, and end up – either accidentally or on-purpose – infringing that cited patent!

Here are lHow do you find out how many Forward Citations your patent has? The Patent Office and www.uspto.gov cannot help you. You need to go to Google Patents. On the right side of the page there is a box that lists all the key data about the patent. Toward the bottom under “Info:” appears a link to the patents cited by the application (Patent Citations) and next to that is a link to the patent filings that cited your patent (Cited by). As we have commented before, Google Patents is a totally free service, but it provides more data than the USPTO website!

If your patent has 50 or more Forward Citations, it is possible it is infringed. If it has 100 or more, it is unlikely that it has not! The more Forward Citations, the more likely that patent has been infringed. Take a look at U.S. Patent No. 9,805,519 at Google Patents – a patent we sold for a client a few years back – and note how many Forward Citations it has!

Returning to the Initial Infringement Analysis and Claim Charts, we are asked all the time by patent owners why they cannot create these themselves. Our response is that you could go to dental school and then perform root canal on yourself, but is it really worth all the effort? These documents have to be created by trained, recognized, professionals who are independent third parties. That is why when you buy a house, you need to get an appraisal from a qualified professional. You simply cannot do it yourself and have any credibility!

As we included in the last installment, brokerage is the Low Risk/ Moderate Reward option, while patent assertion is the High Risk/High Reward option. One of the strategies that companies charged with patent infringement use is to force the infringed patent into an inter partes review at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. If the infringer can get your patent invalidated, it essentially disappears as a threat. That is the major risk of patent assertion that is not a factor in patent brokerage.

Our last item for this installment is the inventor’s involvement in patent assertion. The inventor will very likely be deposed by attorneys for the infringer. That is, the inventor will be questioned by the infringer’s attorneys to determine what type of witness he or she would be should the patent infringement lawsuit go to trial. And if it does go to trial – most do NOT – the inventor will be called to testify.

There Are Two Broad Strategies for Monetizing a Patent – Part I

Posted: 2/26/2025

The inventor who is not going to set up a factory and manufacture and sell a product based on his or her patent is left with two monetization alternatives – sell or license the patent or assert it against its infringers. Asserting it against its infringers is only an option, of course, if the patent is being infringed!

And, therein they say, lies the rub. The reality is that most patents are NOT being infringed, so that leaves the patent owner with an uninfringed patent only one monetization option – find a patent broker to represent him or her and sell or license the patent. A business with a patent it is not practicing has the same two options, but only if the patent is being infringed.

For most patent owners – individuals and businesses – there is just one monetization option and asserting the patent is off the table. But the patent owner – an individual or a business – owning a patent that is being infringed is confronted with some challenging decisions that need to be made.